Stoyan R. Vezenkov and Violeta R. Manolova

Center for applied neuroscience Vezenkov, BG-1582 Sofia, e-mail: info@vezenkov.com

For citation: Vezenkov, S.R. and Manolova, V.R. (2025) Gaming and Gambling Addiction in Fathers as a Risk Factor for Early Screen Addiction in Children. Nootism 1(2), 31-40, ISSN 3033-1765 (print), ISSN 3033-1986 (online) https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.2.3

Abstract

In therapeutic practice with children diagnosed with early screen addiction and complex neurodevelopmental conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and others, it is increasingly evident that their parents often present with undiagnosed behavioral addictions - including screen addiction, gaming, or online gambling. These parents typically seek help not for addiction, but for unrelated complaints such as somatic discomfort, insomnia, memory difficulties, anxiety, depressive symptoms, or attentional deficits. However, initial functional assessments frequently reveal underlying screen-related behavioral addictions, which the clients themselves do not recognize as pathological.

This study presents two case reports of young, professionally functioning fathers, both of whom sought clinical evaluation for issues unrelated to addiction: one for reduced motivation and poor sleep (Client A), and the other for cognitive optimization in professional online poker (Client B). Both underwent a comprehensive assessment protocol including semi-structured clinical interviews, quantitative EEG (qEEG), and autonomic nervous system profiling. Despite their outward stability - employment, family, and social integration - both individuals demonstrated clear neurophysiological and autonomic biomarkers of behavioral addiction. These included slowed cortical activity in frontal and prefrontal regions, increased theta and alpha power with eyes open, deficits in executive functioning, low impulse control, and autonomic dysregulation, particularly heightened sympathetic activity and poor parasympathetic recovery, closely linked to sleep disturbances and chronic fatigue.

A critical shared feature in both cases was the early and unregulated screen exposure of their young children (under age two), which the fathers not only tolerated but actively defended, equating it with their own positive experience of screen use as entertainment and stress relief. This intergenerational normalization of screen addiction poses a significant developmental risk to children during sensitive neurodevelopmental periods. The findings suggest that screen-addicted parents are likely to minimize or rationalize the risks of early exposure, thereby unknowingly facilitating the transmission of addictive patterns to the next generation.

The study underscores the need for preventive strategies that go beyond public education, calling for the early identification and intervention of behavioral addictions in young adults, especially those entering parenthood. The growing prevalence of screen-related behavioral addictions, and their neurophysiological and psychosocial impact on family dynamics, demands urgent recognition within medical, psychological, and public health frameworks.

Keywords: screen addiction, behavioral addiction, qEEG, executive function, parental behavior, early childhood development, online gaming, online gambling, intergenerational risk

Introduction

The spread of gaming addiction as a subtype of screen addiction has been well documented in recent years. According to the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), gaming disorder is defined as a pattern of gaming behavior – whether digital or video gaming – characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that it takes precedence over other interests and daily responsibilities, and continued or escalated gaming despite the emergence of negative consequences.

Gaming addiction, also referred to as Internet Gaming Addiction (IGA), has also been acknowledged in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), as a condition requiring further clinical attention. The most frequently reported symptoms associated with gaming addiction include insomnia, hyperactivity, depression, and in some cases, withdrawal-like symptoms (Kaptsis et al., 2016; Gentile et al., 2011; Alimoradi et al., 2019; Billieux et al., 2015).

Studies employing quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) have shown that individuals with internet and gaming addiction tend to exhibit increased theta and delta power in the frontal and central brain regions. These patterns are typically associated with diminished executive functioning and reduced impulse control (Dong et al., 2014). Another significant finding from qEEG research is the presence of abnormalities in coherence and functional connectivity among individuals with screen addiction. Excessive screen exposure has been linked to disrupted frontal-parietal and fronto-limbic connectivity, which may contribute to emotional dysregulation, attention deficits, and impaired reward processing (Lee et al., 2017; Park et al., 2017; 2018; Youh et al., 2017).

This article presents two clinical cases involving fathers who had no diagnosis of internet gaming disorder or gambling addiction, and who did not seek help for such issues. Instead, they came for clinical evaluation due to other complaints and concerns.

The findings from the evaluation were unexpected, which is why the cases will be described in detail, with particular attention to patterns of functioning and challenges that are characteristic of many young individuals in today's digitized world.

Methods

A preliminary evaluation was conducted, which included a semi-structured clinical interview, quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG), and recording of peripheral autonomic signals.

qEEG Assessment

Electroencephalographic recordings were carried out using a 19-channel monopolar montage with the Neuron-Spectrum-4P system and Neuron-Spectrum.NET software (Neurosoft LLC, Russia). Quantitative spectral analysis – comprising amplitude calculations across various brain rhythm bands and other electrophysiological parameters – was performed using Neuron-Spectrum.NET. For normative comparison, registered quantitative parameters (including absolute and relative amplitudes, coherence, phase lag, and Z-scores) were analyzed using NeuroGuide Deluxe 3.3.0 (Applied Neuroscience, Inc., USA), referencing a normative neurodatabase.

Assessment of Autonomic Balance

Peripheral autonomic signals were measured, including heart rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), peripheral temperature, respiratory rate, skin conductance level (SCL), and electromyography (EMG). These recordings were obtained using the Gp8 Amp 8-channel system and Alive Pioneer Plus software (Somatic Vision Inc., USA). Analysis of HRV parameters – such as HR, SDNN, total power, LF/HF ratio, smoothness, stress index, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) index, and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) index – was conducted within Alive Pioneer Plus and further processed using Kubios HRV Scientific Lite software.

Results

Case A

A 41-year-old man, appearing to be in generally good health, presented for evaluation with complaints of poor sleep quality. He reported waking up around 4 a.m. almost every night for the past two years. In addition, he described difficulties with concentration during the day and a lack of motivation to perform his job, which, in his own words, has been fully automated and computerized for the past five to six years. He had no prior diagnosis and had never sought psychological or medical help.

Since adolescence, video games have been a regular part of his life, and he described himself as performing well above average in gaming. He reported that he enjoys playing for several hours each day, considering it a form of relaxation and a way to disconnect from daily responsibilities. His routine activities are carried out on "autopilot," and he looks forward to playing games as the most enjoyable part of his day.

During his teenage years, he played between 10 and 12 hours daily. In recent years, this has decreased significantly to about 5–6 hours per day. Over the past two years – when his symptoms began – he has been gaming an average of two hours per day, including playing online bridge.

He is married and has a two-year-old child. He reports being on autopilot at work for several years, with no career development, which he attributes to not dedicating enough time or effort. He does not take any medications but does use some commonly available dietary supplements.

He denied having any problems in his relationship with his wife. However, their child experiences disturbed sleep and frequently wakes at night, often sleeping in the parents' bed. When asked whether the child is exposed to screens, he responded affirmatively, expressing surprise at the question. He did not make any connection between the birth of his child and the onset of his own symptoms, nor between the child’s sleep problems and his own.

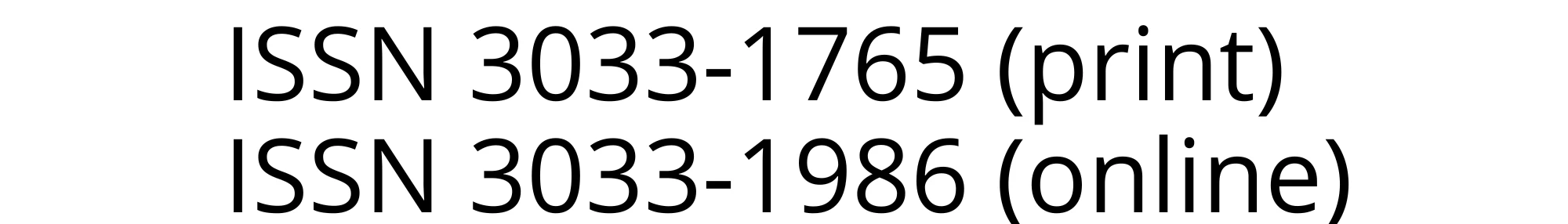

The absolute power (squared amplitude) in the frontal and prefrontal derivations within the alpha frequency band (8–13 Hz) with eyes closed was two standard deviations above the normative range. Notably, at 9 and 10 Hz, the elevated power extended into the temporal derivations T3 and T4 (Figure 1, top right). These were also the dominant frequencies, which appeared either alternating or simultaneously (Figure 1, bottom right). A distinct pattern was observed: elevated power was confined to the central and anterior regions, while the temporal, parietal, and occipital derivations showed a marked reduction in amplitude (Figure 1, bottom right). This pattern was the inverse of the typical topographic distribution, where in normative EEG, amplitudes increased posteriorly. Here, the highest amplitudes were localized in the prefrontal regions.

Due to the significantly increased power in the alpha band, all related indices - including alpha/beta1, alpha/beta2, and beta1/beta2 - were well above the normative range, exceeding two standard deviations (Figure 1, bottom left).

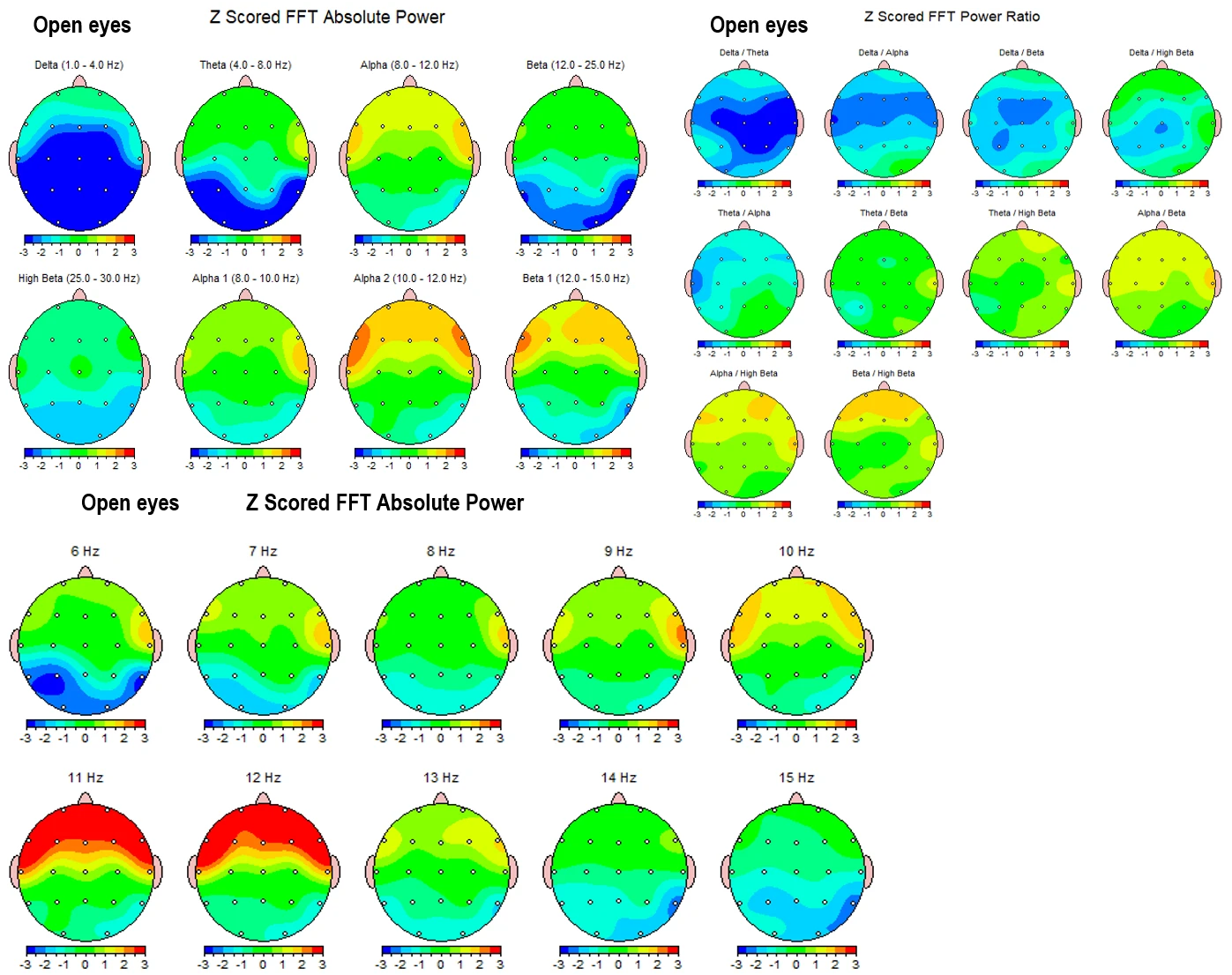

With eyes open, the absolute power remained two standard deviations above normal only in the alpha-2 range (11–12 Hz) (Figure 2, bottom). As a result, the alpha/beta and alpha/beta2 indices were elevated by approximately 1.5 standard deviations, again localized only in the frontal and prefrontal regions. The spectral pattern observed with eyes open showed no episodes of full desynchronization, and this sustained activity was illustrated in Figure 1, bottom right.

Figure 1 presents the client's cortical activity with eyes closed, compared to normative data from the neurodatabase.

Figure 1. Quantitative EEG parameters of Client A with eyes closed. Top right: absolute power across frequency bands; Top left: absolute power for each frequency in 1 Hz resolution; Bottom right: frequency indices; Bottom left: typical EEG spectra with eyes closed and eyes open.

Figure 2 presents the client's cortical activity with eyes open, compared to normative data from the neurodatabase.

Figure 2. Cortical activity of Client A with eyes open. Top left: absolute power across frequency bands; Top right: frequency indices; Bottom: absolute power for each frequency in 1 Hz resolution.

Peripheral temperature measured from the little finger remained between 23°C and 25°C during the first 25 minutes of the assessment. However, following the conclusion of the EEG recording, the temperature rose to 31°C. This pattern suggests situational, rather than generalized, signs of a freezing-type autonomic response. Skin conductance, which initially showed low absolute values, increased after the rise in peripheral temperature – even in the absence of external stimuli and under resting conditions – indicating a third - degree level of neuropsychological tension.

The client alternates between two autonomic response patterns: one characterized by low sympathetic and parasympathetic tone, and another marked by a highly reactive, mobile sympathetic tone, consistent with anxiety - related tendencies.

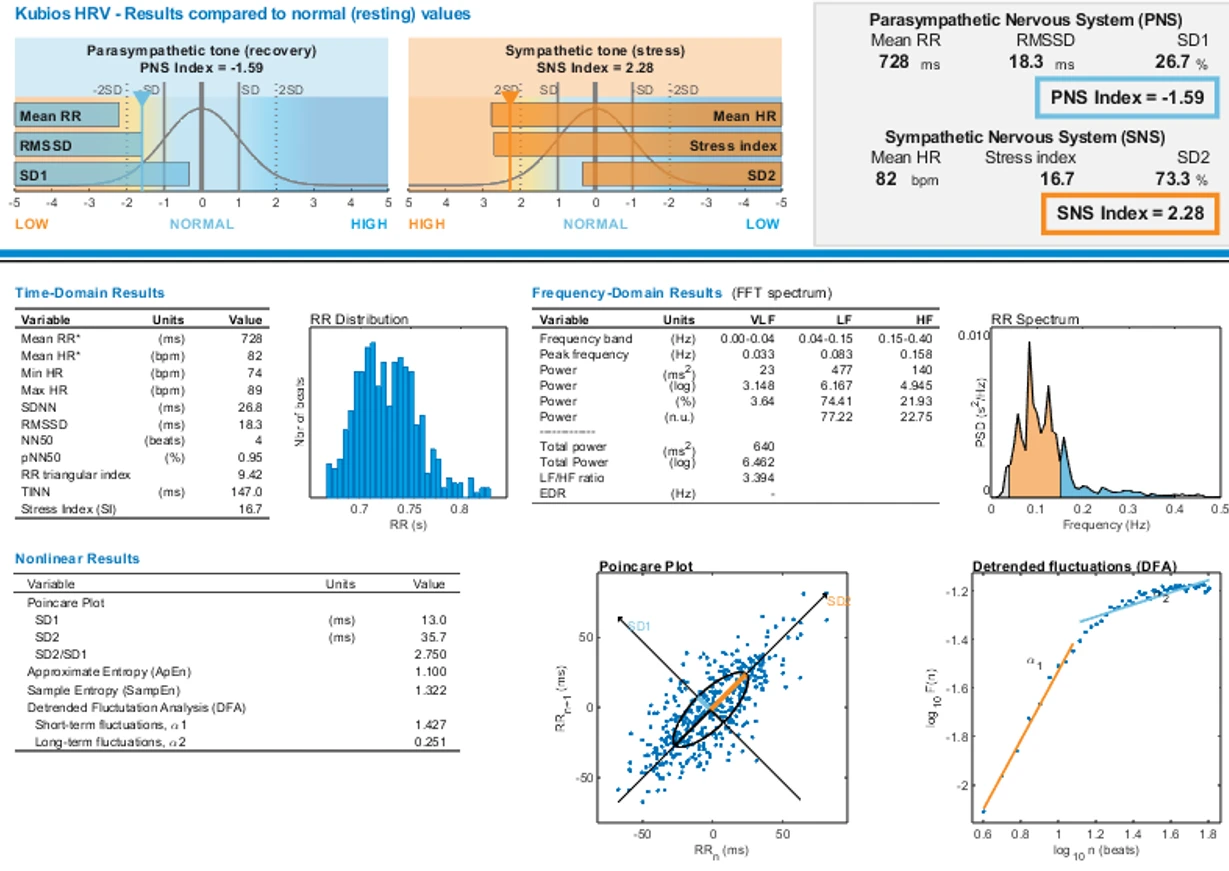

Figure 3 presents the heart rate variability (HRV) parameters at rest.

Figure 3. Heart rate variability (HRV) parameters of Client A at rest. The sympathetic index and stress index are above the normative range, while the parasympathetic index is below normal.

Case B

A 37-year-old man with no reported complaints presented for evaluation, seeking assistance in optimizing his performance in online poker. He is married and has two children – the older is four years old, and the younger is six months.

It became evident during the assessment that he has a history of various behavioral addictions. These include excessive gaming during his teenage years, compulsive pornography viewing accompanied by masturbation, and periods of binge - watching television series. He has been playing poker professionally since the age of 22, with a six-year break, and has resumed regular play in recent years. Currently, poker is his primary source of income.

He stated that he is aware of when he should stop playing in order to minimize losses but is unable to exercise control in practice. On average, he plays for several hours each day. He reported no problems in his relationship with his wife or with his children.

When asked whether his children are exposed to screens, his response was affirmative. When questioned about potential developmental concerns, he gave a brief and dismissive answer, indicating no apparent negative attitude toward the screen use of his young children.

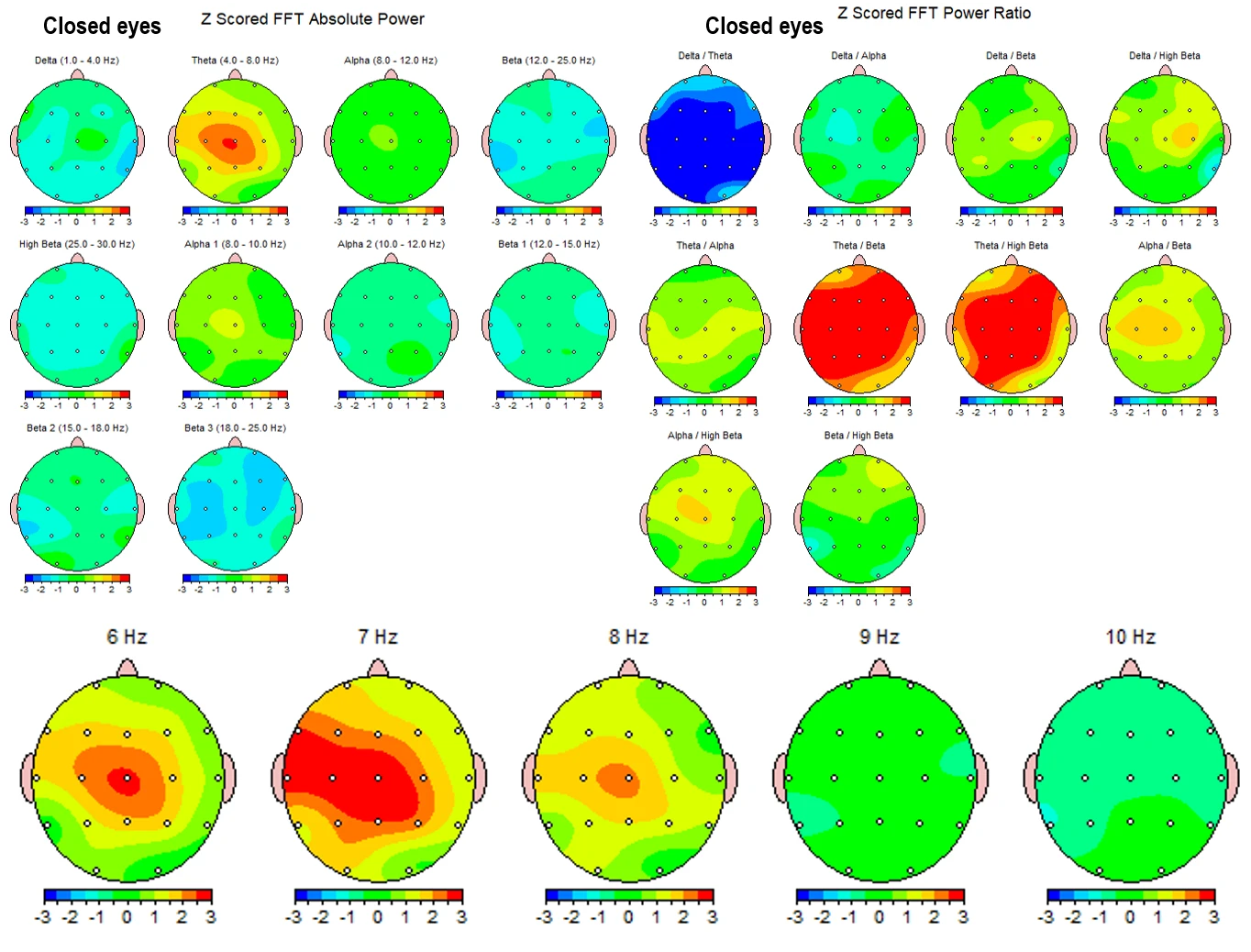

Figure 4 presents the cortical activity of Client B with eyes closed.

Figure 4. Quantitative EEG parameters of Client B with eyes closed. Top right: absolute power across frequency bands; Top left: absolute power for each frequency in 1 Hz resolution; Bottom right: frequency indices; Bottom left: typical EEG spectra with eyes closed and eyes open.

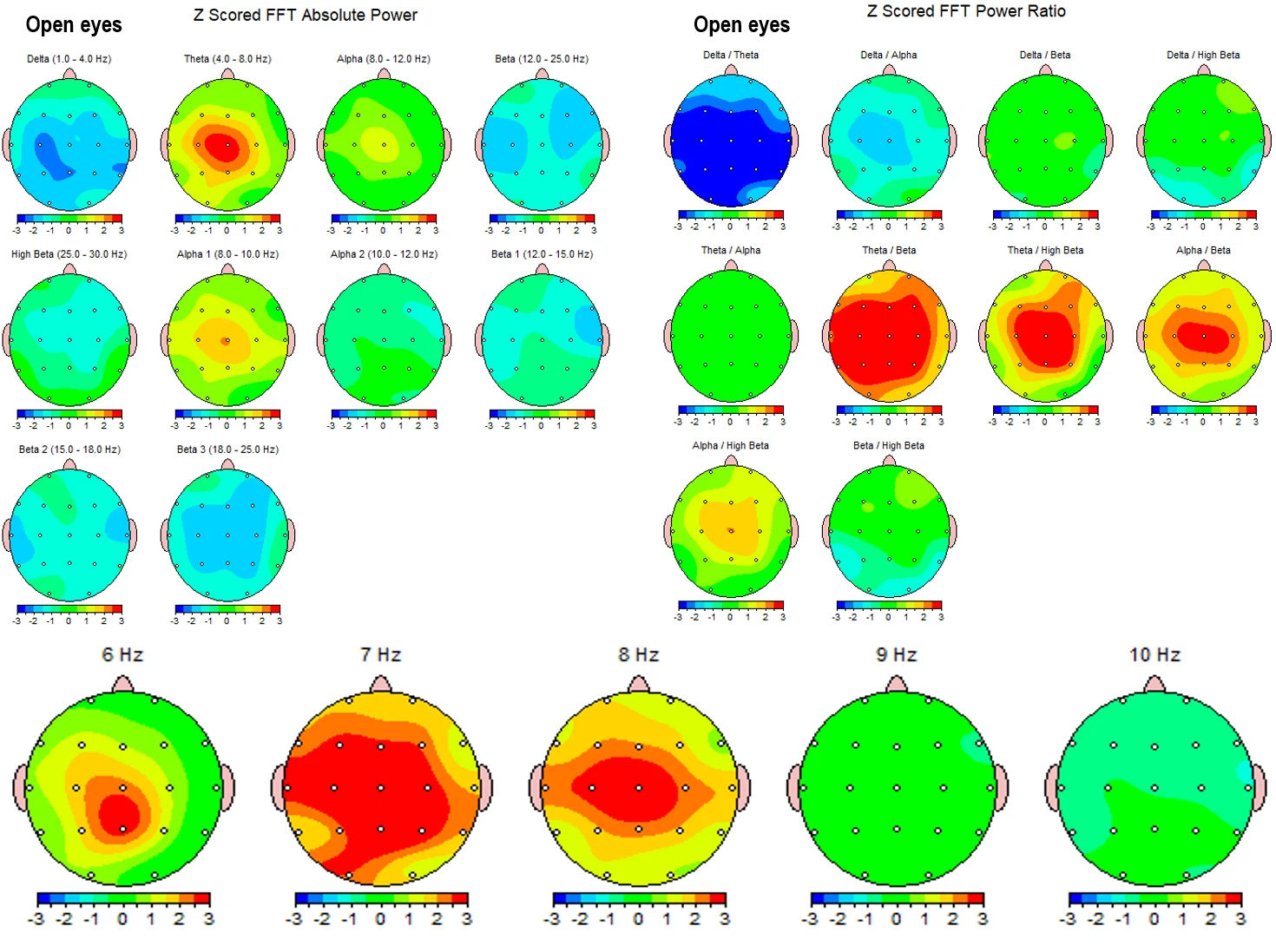

Figure 5 presents the cortical activity of Client B with eyes open.

Figure 5. Cortical activity of Client B with eyes open. Top left: absolute power across frequency bands; Top right: frequency indices; Bottom: absolute power for each frequency in 1 Hz resolution.

With eyes closed, the absolute power in the theta band (6–8 Hz) was two standard deviations above the normative range in the central and left-central derivations. At 7 Hz, these significant elevations extended to C3, F3, P3, T3, and F7, as well as to the midline derivations Fz, Cz, and Pz (Figure 4, bottom).

Due to the presence of a dominant 7 Hz frequency, the theta/beta and theta/beta2 indices were elevated by more than two standard deviations across nearly all derivations. Additionally, the alpha/beta and alpha/beta2 indices were elevated in Cz and C3, as a result of increased alpha-1 power in these regions (Figure 4, top right).

With eyes open, the functional pattern did not change. The same slow-wave activity persisted in the theta range (6–8 Hz), along with increased alpha-1 power around 8.5 Hz (Figure 5, bottom). Consequently, the theta/beta, theta/beta2, and alpha/beta indices remained more than two standard deviations above the norm (Figure 5, top right).

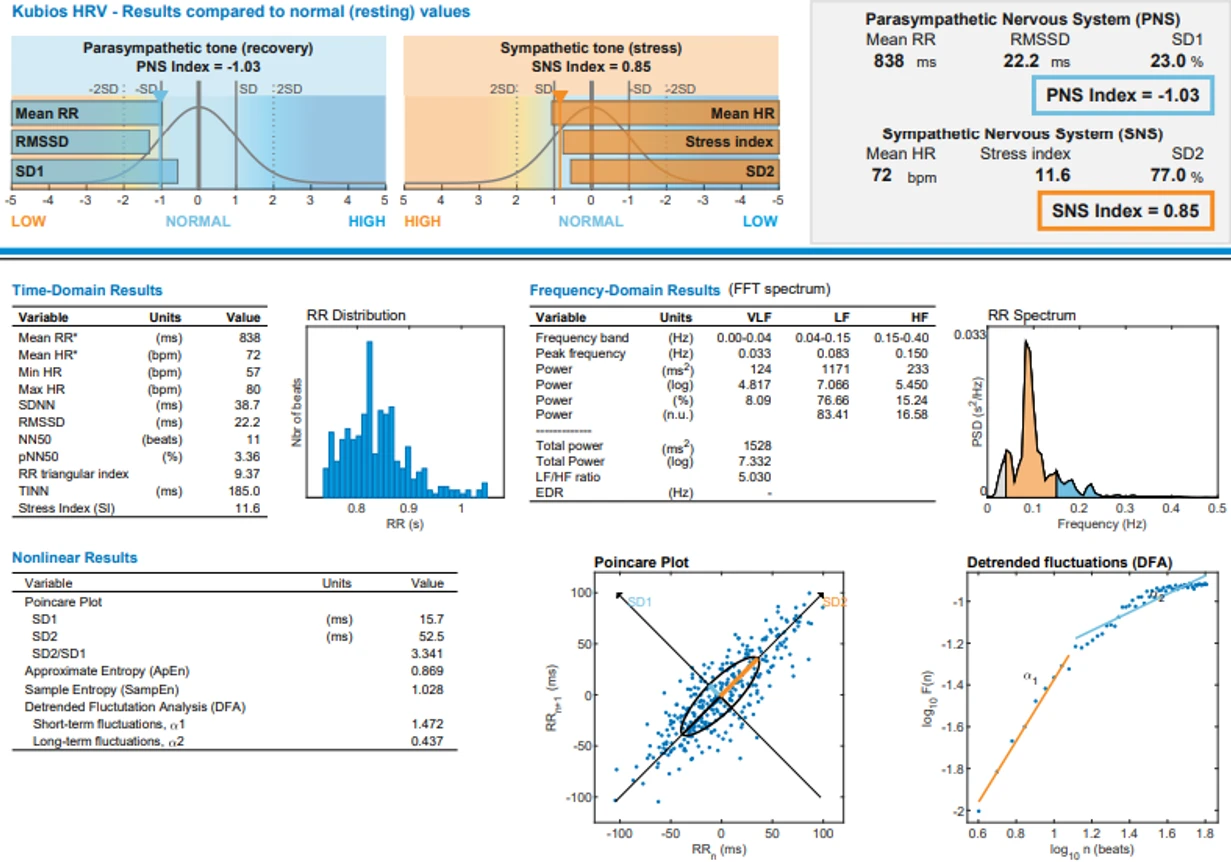

Peripheral temperature was measured at 26°C while the client was recounting his personal history, including experiences with addiction and his engagement with poker. It quickly rose to 32°C once the resting-state EEG recording began. Skin conductance levels initially showed low absolute values, accompanied by freezing and suppression responses during the narrative about his personal life. The sympathetic and stress indexes were at the upper limit of the normative range, while as the parasympathetic index remained below normal during resting conditions.

The heart rate variability (HRV) parameters are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Heart rate variability (HRV) parameters of Client B at rest.

Discussion

The sympathetic index in both cases was at or above the upper normative threshold, indicating increased excitability and hyperreactivity. Conversely, the parasympathetic index was below the normative range, reflecting a lack of restorative processes during rest. The stress index was also elevated. All three parameters correlate with the sleep disturbances reported by both individuals.

In addition, signs of freezing responses and avoidant behavior, along with a lack of motivation for social interaction or achievement in social contexts, suggest mild depressive functioning – a pattern frequently observed in individuals with various forms of behavioral addiction. Notably, these physiological and emotional indicators tend to shift when the individual engages in the activity they are dependent on, such as gaming or gambling.

These findings align with previous research comparing gaming disorders to gambling disorders (Wausserman & Faust, 2014; Granic, 2014), suggesting overlapping neurophysiological and behavioral mechanisms between the two.

Physiological patterns change significantly when individuals are exposed to the overstimulation associated with their addictive behaviors. During such activities, they appear more animated and report feeling safe, successful, and fulfilled. In contrast, everyday life is perceived as effortful, monotonous, and slow – lacking the intensity and excitement of their preferred stimuli. As a result, they function on “autopilot.”

In both cases, brain activity indicates that executive functions – localized in the frontal and prefrontal regions – are in a resting state, as shown by elevated alpha and theta activity with eyes open (Figures 1, 2, 4, and 5). This neurophysiological pattern correlates with a deficit in attention toward real - world and social stimuli, a lack of motivation for self-realization, and an absence of volitional drive to initiate change.

Attention deficits were observed in both individuals – of the alpha-type in Case A and the theta-type in Case B. These patterns also serve as biomarkers for low impulse control, emotional reactivity, and affective outbursts.

Interestingly, in Case A, the alpha1/beta and alpha2/beta indices were significantly elevated – exclusively in the frontal and prefrontal derivations – strongly indicating chronic fatigue, mental overload, and functional disengagement. In contrast, the central, parietal, and occipital regions exhibited parameters within the normative range, suggesting that perceptual and sensory - integrative functions are preserved. The impairment appears to be limited to executive domains: goal - setting, decision - making, initiative, and entrepreneurship.

These individuals rely on familiar, though complex, automated behaviors. Their functioning is marked by elaborate automaticity, constant comparison with memory-based templates, and a retrospective orientation – including nostalgia for past accomplishments and emotionally charged experiences. This pattern is emblematic of addiction-related cognitive and emotional dynamics.

In Case B, the theta/beta index was significantly above the normative range, indicating a more pronounced attention deficit, lack of impulse control, and executive dysfunction compared to Case A. The presence of 6–8 Hz rhythms and elevated alpha1 activity further serve as indicators of screen-induced trauma and screen addiction (Manolova et al., 2025; Vezenkov et al., 2025). These patterns are also associated with chronic fatigue and disturbed sleep quality, forming a vicious cycle that reinforces stereotyped, change-avoidant behavior.

In other words, the individuals tend to react automatically to changes in family and work dynamics. While this gives the appearance of adaptability and flexibility, it is, in reality, only superficial. Their personal agency and developmental trajectory appear to have stagnated, effectively governed by the addiction that now orchestrates their behavior and life choices.

Up to this point, nothing observed may seem particularly alarming - mainly because such patterns have become widespread and normalized. These are adults, after all, free to make their own choices and even to drift through life on autopilot. However, the situation becomes significantly more concerning when these individuals become fathers.

People with behavioral addictions can be toxic parents, particularly when they serve as role models whose behavior is closely imprinted by their children. Alarmingly, such fathers often exhibit tolerance toward early and excessive screen exposure, even during the sensitive developmental window between 0 and 2 years of age. Both individuals in this study reported seeing no problem with their young children using screens at these ages - especially given that they themselves engage in prolonged screen-based activities in front of their children.

This dynamic places their children at high risk for developmental disturbances. While there may be no conscious intent to induce addiction in their children - and even if such a risk is not perceived - the screen becomes a kind of "babysitter" that allows the parent to engage in their own addictive behavior undisturbed.

It is well established that individuals with addiction often fail to recognize their condition, rationalizing or minimizing its effects. As a result, they also fail to recognize - or actively tolerate - addictive or dysfunctional behavior in others, including close family members and, notably, their children.

Such patterns of parenting in families where screen-dependent children are present have been described elsewhere (Manolova et al., 2025).

The emerging forms of behavioral addiction related to the virtual world - such as gaming and online gambling (e.g., poker)—have been shown to significantly alter the addict’s neurophysiology, affecting not only autonomic and affective functioning but also the cortical networks, particularly those responsible for executive functions.

These individuals become behavioral models for their own children, immersing them in toxic relationships and developmentally harmful environments, much like what is observed in families affected by substance addictions (e.g., alcohol, drugs) or other behavioral addictions. The autonomic and functional patterns exhibited by the parents are directly transmitted to their children, but with a critical difference: in children, the developmental impact of such dysfunctional functioning is profound and far-reaching.

In both cases presented, the fathers reported poor sleep quality in their young children, yet failed to draw any connection between their own disrupted sleep patterns and those of their children. This highlights a deeper issue: these parents equate their children's screen exposure with their own experience of screen-based activities, which they perceive as relaxing, recreational, or harmless. This misjudgment fails to account for the child’s stage of neurological and emotional development, where the consequences of overstimulation and screen addiction can be long-lasting and severe.

What makes this especially insidious is that such exposure is normalized by the parents' own behavior. In today’s world, few people reflect on why all substances and behaviors associated with addiction are legally restricted to adults aged 18 and over. Yet, ironically, screen-based addictions remain largely unnoticed and unregulated, operating beneath the radar of medical, psychological, and social services—despite their clear potential for harm, especially in early childhood.

Moreover, these individuals not only minimize the risks of their behavior, but are firmly convinced that gaming and gambling are integral parts of daily life, even tools that help them cope and perform better. For them, addictive behavior is not only normalized - it is prioritized, placed above other responsibilities and life domains.

In their understanding, addiction as a disorder is reserved solely for substance-based addiction, whereas behavioral addictions are simply seen as a lifestyle choice. They maintain stable, even lucrative, employment, have families and children - all of which serve as a social and personal mask, concealing the fact that these roles lack genuine emotional investment or existential meaning.

Through this disconnect, they inadvertently become agents of transmission, passing their own addictions onto their children—not through overt intention, but through deeply internalized, normalized patterns of behavior. Fully convinced of the harmlessness of their actions, they remain unaware of the consequences, yet actively contribute to the intergenerational perpetuation of addiction.

Conclusion

This study presents evidence of screen-related behavioral addiction – specifically, gaming and online poker (gambling) – in two fathers who sought therapeutic consultation for unrelated reasons: one (Client A) for sleep and motivation issues, and the other (Client B) for performance optimization in professional poker. Both are fathers of very young children and demonstrate a strong tolerance toward early screen exposure, expressing no concern despite being aware, at least nominally, of its potential harms.

A key finding is that both individuals project their own screen-related experiences as adults onto their children, confidently asserting that early screen use poses no risk. This attitude reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of developmental vulnerability, and a failure to differentiate between adult coping behaviors and early childhood neurodevelopmental needs.

In the case of substance-based addictions, it is widely understood that children must be protected from exposure until at least 18 years of age. However, with modern behavioral addictions – particularly screen addiction – there is no such societal reflex to safeguard minors. This lack of awareness results in unregulated and often harmful exposure, especially during critical periods of early development.

The findings suggest that the prevalence of early screen addiction risk is likely much higher than what is currently reflected in the literature. Consequently, preventive policies must begin not only with broad public education, but also with directly addressing behavioral addictions in young adults – especially those who are, or will soon become, parents.

References

Alimoradi,Z., Lin,C.Y., Broström, A., Bülow, P.H.,Bajalan,Z., Griffiths, M.D., Ohayon, M.M. and Pakpour,A.H. (2019) Internet addiction and sleep problems: asystematic review and meta - analysis, Sleep Medicine Reviews, Vol.47, pp. 51 - 61, doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.004,ISSN1087 - 0792.

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez - Fernandez, O., Kuss, D.J. and Griffiths, M.D. (2015), Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research, Current Addiction Reports, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 156 - 162, doi: 10.1007/s40429 - 015 - 0054 - y.

Dong, G., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). A cognitive - behavioral model of Internet gaming disorder: Theoretical underpinnings and clinical implications. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 58, 7 - 11. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.005

Gentile, D.A., Bailey, K., Bavelier, D., Brockmyer, J.F., Cash, H., Coyne, S.M. ... and Young, K. (2017), Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents, Pediatrics, (Supplement_2),Vol.140,pp.S81 - S85.

Gentile, D.A., Choo, H., Liau, A., Sim, T., Li, D., Fung, D. and Khoo, A. (2011), Pathological video game use among youths: a two - year longitudinal study, Pediatrics, Vol. 127 No.2,pp.E319 - E329.

Granic, I., Lobel, A. and Engels, R.C. (2014), The benefits of playing video games, American Psychologist, Vol. 69 No. 1, pp.66 - 78.

Griffiths, M.D., Kuss, D.J. and Pontes, H.M. (2016), A brief overview of Internet gaming disorder and its treatment, Australian Clinical Psychologist, Vol. 2 No. 1, p. 20108.

Gupta, K., Kumar, C., Deshpande, A., Mittal, A., Chopade, P. and Raut, R. (2024), Internet gaming addiction – a bibliometric review, Information Discovery and Delivery, Vol. 52 No. 1, pp. 62 - 72. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD - 10 - 2022 - 0101

Kaptsis,D., King,D.L., Delfabbro,P.H. and Gradisar,M. (2016) Withdrawal symptoms in internet gaming disorder: a systematic review, Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 43, pp. 58 - 66, doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.006, ISSN 0272 - 7358

Kuss, D.J. and Griffiths, M.D. (2012) Internet gaming addiction: a systematic review of empirical research, International Journal of Mental Health And Addiction, Vol. 10 No.2, pp. 278 - 296.

Lee, J. Y., Park, S. M., Kim, Y. J., Kim, D. J., Choi, S. - W., Kwon, J. S., & Choi, J. - S. (2017). Resting - state EEG activity related to impulsivity in gambling disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.055.

Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Parental Models: A Profile of the Dynamics in Children Dropping Out of Therapy Programs for Screen Addiction. Nootism 1(1), 96 - 100, ISSN 3033 - 1765 (print), ISSN 3033 - 1986 (on - line)

Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Screen Trauma – Specifics of the Disorder and Therapy in Adults and Children. Nootism 1(1), 37 - 51, ISSN 3033 - 1765 (print), ISSN 3033 - 1986 (on - line)

Mehroof, M. and Griffiths M.D. (2010) Online gaming addiction: the role of sensation seeking, self - control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, Vol. 13 No.3,pp313 - 316.

Park, S. M., Lee, J. Y., Kim, Y. J., Lee, J. Y., Jung, H. Y., Sohn, B. K., Choi, J. - S. (2017) Neural connectivity in internet gaming disorder and alcohol use disorder: A restingstate EEG coherence study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1333. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598 - 017 - 01419 - 7.

Park, S., Ryu, H., Lee, J. Y., Choi, A., Kim, D. J., Kim, S. N., & Choi, J. S. (2018). Longitudinal changes in neural connectivity in patients with internet gaming disorder: A resting - state EEG coherence study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 252. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00252.

Vezenkov, S.R., Manolova, V.R. (2025) Screen Addiction – Biomarkers, Developmental Damage and Recovery. Nootism 1(1), 6 - 18, ISSN 3033 - 1765 (print), ISSN 3033 - 1986 (on - line)

Wausserman, S. and Faust, K. (2014), Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Youh, J., Hong, J. S., Han, D. H., Chung, U. S., Min, K. J., Lee, Y. S., & Kim, S. M. (2017). Comparison of Electroencephalography (EEG) Coherence between Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) without Comorbidity and MDD Comorbid with Internet Gaming Disorder. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 32 (7), 1160. doi:10.3346/jkms.2017.32.7.1160