Stoyan R. Vezenkov and Violeta R. Manolova

Center for applied neuroscience Vezenkov, 1582-Sofia, e-mail: info@vezenkov.com

For citation: Vezenkov S.R. and Manolova V.R. (2025) From Addiction to Trauma: How a Father’s Pornography Addiction Disrupted Marital Bonds, Parenting, and Child Neurodevelopment. Nootism 1(4), 38-54; https://doi.org/10.64441/

Abstract

This case study explores the complex interplay between parental addiction, unresolved trauma, and neurodevelopmental disturbances in children within a five-member family system. The father’s long-standing pornography addiction and the mother’s trauma-related co-addiction created a dysfunctional relational environment that contributed to screen addiction, learning difficulties, emotional dysregulation, and stuttering in their three sons. Notably, all three children experienced periods of stuttering, with symptoms resolving in the youngest and oldest sons, while the middle son continued to exhibit a severe fluency disorder at the time of assessment. Neurophysiological evaluations (qEEG and HRV) revealed distinct patterns of dysregulation in all family members, reflecting their psychological roles and adaptive strategies. The oldest son showed signs of attention deficit and screen trauma; the middle son manifested trauma through persistent stuttering and somatic symptoms, while the youngest demonstrated the fastest recovery following digital detox, although residual trauma markers persisted. The father’s flattened autonomic responses reflected addictive dissociation, whereas the mother’s sympathetic overactivation and freezing patterns indicated chronic trauma and co-addiction. Despite initial motivation for therapy, the family declined intervention after core relational dynamics were revealed, illustrating the self-reinforcing nature of trauma-addiction systems. This study demonstrates that, contrary to the widely held view that trauma precedes addiction, addiction itself can act as a primary source of trauma, particularly within close family relationships and developing children. This study underscores also the value of systemic, neurobiologically informed approaches to intergenerational trauma and behavioral addictions in family contexts.

Keywords: family systems, pornography addiction, co-addiction, intergenerational trauma, stuttering, screen addiction, qEEG, HRV, attention deficit

Introduction

The proliferation of high-speed internet has rendered online pornography ubiquitously accessible, raising significant clinical and public health questions regarding its potential for problematic patterns of use (Duffy et al., 2016). While colloquially termed "pornography addiction," the scientific community increasingly favors the term "problematic pornography use" (PPU) to describe a condition characterized by a loss of control over pornography consumption, continued use despite negative consequences, and significant functional impairment (Potenza, 2018; Mestre-Bach et al., 2020; 2023; 2024; 2025). This terminological shift reflects a complex and ongoing debate regarding the nosological classification of the behavior. Notably, PPU is not recognized as a distinct mental disorder in the fifth edition, text revision, of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). However, its core features are encapsulated within the diagnosis of Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder (CSBD) in the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), defined by a persistent failure to control intense sexual impulses leading to repetitive behavior that causes marked distress or impairment (World Health Organization, 2019).

Recent primary scientific reviews have firmly established a link between PPU and a range of adverse psychological and interpersonal outcomes. A consistent finding across multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses is the strong, positive correlation between PPU and mental health comorbidities, particularly elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and perceived stress (Vieira et al., 2024; Stark et al., 2018). The directionality of this association remains a key question, with evidence supporting both the hypothesis that PPU contributes to psychopathology and the "self-medication" hypothesis, wherein individuals with pre-existing mood disorders may use pornography to cope with negative affect (Stark et al., 2018).

From a neurobiological perspective, research has sought to determine whether PPU shares the neural substrates of established substance and behavioral addictions. Theoretical models, such as the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model, provide a framework for understanding how predisposing personality factors, affective states, cognitive biases, and reduced executive functions contribute to the development and maintenance of addictive behaviors, including PPU (Brand et al., 2019). Neuroimaging studies have lent support to these models, identifying functional and structural alterations in brain networks associated with reward processing, craving, and executive control, such as the prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum (Brand et al., 2019). While these findings suggest some parallels with substance use disorders, the specific interplay of these factors underscores the complexity of PPU.

While these findings suggest some parallels with substance use disorders, other research highlights crucial differences, indicating that PPU may represent a distinct neurobiological phenotype rather than a direct analogue of chemical addiction (Kühn et al., 2014). These divergent findings underscore the need for further research to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Beyond individual-level factors, the impact of PPU extends into the interpersonal domain. A growing body of evidence links PPU with decrements in relational and sexual well-being. Meta-analytic findings indicate that higher levels of PPU are associated with lower relationship satisfaction for both the user and their partner, as well as reduced sexual satisfaction and, in some cases, difficulties with sexual function like erectile dysfunction (Marshall & Miller, 2019; Chen et al., 2021).

Pornography use has become increasingly common with the rise of internet accessibility, yet its impact on individuals and relationships remains a topic of ongoing debate. While many users engage with pornography without apparent negative consequences, a subset experiences problematic pornography use (PPU), characterized by compulsive patterns, loss of control, and significant distress or impairment. Recent research highlights not only the personal consequences of PPU but also its broader relational effects. As Mestre-Bach and Potenza (2023) emphasize, pornography use – especially when perceived as excessive or hidden – can negatively affect relationship satisfaction, intimacy, and trust, potentially leading to conflict, emotional distance, or even separation. Their review underscores the importance of examining pornography use within relational contexts, as partners' perceptions and communication patterns play a crucial role in mediating its impact.

Emerging research suggests that parenting style and familial dynamics play a critical role in the development and maintenance of problematic pornography use (PPU). Authoritarian and permissive parenting styles have been modestly linked to increased pornography addiction risk, potentially due to a lack of emotional regulation support and inconsistent boundaries in the home environment (Seyedzadeh Dalooyi., 2023). Conversely, authoritative parenting – characterized by warmth, structure, and open communication – appears to serve as a protective factor. Moreover, the influence of parental behavior extends beyond parenting style: a parent's own pornography use, particularly when secretive or compulsive, may undermine their credibility as a role model and disrupt parent–child trust (Mestre-Bach & Potenza, 2023). Despite these implications, systematic reviews highlight a significant gap in empirical research directly examining the intergenerational effects of PPU, especially regarding fathering practices and child developmental outcomes. This underlines the need for more nuanced, family-centered investigations into how pornography use interacts with parenting and impacts relational and psychological health across generations.

How certain forms of parental screen addiction contribute to the development of addictive functioning and early screen addiction in children has been raised in prior studies (Vezenkov & Manolova, 2025(1); 2025(2)). The hidden dynamics within the family system play a key role both in the emergence and recovery from early screen addiction in children (Petrov et al., 2025; Pashina et al., 2025; Manolova et al., 2025; Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025(1); 2025(2)). Parental addiction is often associated with insecure attachment styles, which hinder typical child development and represent a significant risk factor for early screen addiction (Mestre-Bach & Potenza, 2023; Petkova et al., 2025). Furthermore, screen addiction leads to infantilization and delayed emotional maturation, often resulting in individuals entering parenthood in an insecure, anxious, and ultimately unprepared state (Alexandrov et al., 2025).

Although family dynamics in the treatment of children with early screen addiction resist simplistic generalization or confinement within a single research framework, their recognition, management, and the development of parental capacities to consciously reflect on and update these dynamics are crucial to recovery. For this reason, neurofeedback and biofeedback for the parents form an essential part of family-based interventions. (Vezenkov&Manolova, 2024; 2025(3)) In this article, we present a case study of a five-member nuclear family, aiming to capture the key factors that contributed to early screen addiction in the children – including underlying trauma.

Methods

Initial Assessment

A preliminary evaluation was conducted, which included a semi-structured clinical interview, quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG), and recording of peripheral autonomic signals.

qEEG Assessment

Electroencephalographic recordings were carried out using a 19-channel monopolar montage with the Neuron-Spectrum-4P system and Neuron-Spectrum.NET software (Neurosoft LLC, Russia). Quantitative spectral analysis—comprising amplitude calculations across various brain rhythm bands and other electrophysiological parameters—was performed using Neuron-Spectrum.NET. For normative comparison, registered quantitative parameters (including absolute and relative amplitudes, coherence, phase lag, and Z-scores) were analyzed using NeuroGuide Deluxe 3.3.0 (Applied Neuroscience, Inc., USA), referencing a normative neurodatabase.

Assessment of Autonomic Balance

Peripheral autonomic signals were measured, including heart rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), peripheral temperature, respiratory rate, skin conductance level (SCL), and electromyography (EMG). These recordings were obtained using the Gp8 Amp 8-channel system and Alive Pioneer Plus software (Somatic Vision Inc., USA). Analysis of HRV parameters – such as HR, SDNN, total power, LF/HF ratio, smoothness, stress index, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) index, and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) index – was conducted within Alive Pioneer Plus and further processed using Kubios HRV Scientific Lite software.

Results

Family dynamics and issues

The family sought help due to various symptoms observed in their three sons: Boris (aged 11), Peter (aged 8), and Simeon (aged 6). The oldest son, Boris, had learning difficulties and required continuous support and additional tutoring from his grandmother, a retired primary school teacher, to keep up with his schoolwork. He lacked concentration and showed signs of attention deficit, although no formal diagnosis was made. Three years earlier, he developed headaches accompanied by vomiting and stuttering, which resolved after about one year of speech therapy. He often tried to dominate his brothers and tended to form temporary alliances with one against the other. Both overt and subtle verbal and nonverbal aggression among the siblings were frequently observed. He had sleep disturbances, falling asleep easily within five minutes when a bedtime story was read, but waking frequently during the night and feeling unrested in the morning. As a young child, he also experienced frequent night waking and crying. He craved sweets and chocolate, persistently sought them out, and found ways to access them. He was exposed to screens from around the age of one, with approximately two hours of daily background television. In the last six months, he often played computer and PlayStation games with his father and brothers.

Peter, the middle son, aged 8, had severe stuttering, which began around 2.5 years earlier and worsened during episodes of illness. Around the same time, he broke his arm – a situation that repeated the following year during another football incident involving his older brother. The first incident required multiple surgeries under general anesthesia. During this period, the stuttering worsened, presenting with prolonged blocks and associated motor tics. He slept well, fell asleep easily, stayed asleep through the night, and woke up rested. He functioned well academically and did not experience learning difficulties. He refused to eat fish or cooked meat but enjoyed grilled meat. At the time of evaluation, he exhibited symptoms typical of severe stuttering, including logophobia, avoidance behaviors, and reluctance to speak. He had nocturnal enuresis until the age of six and continued to breathe orally due to previously enlarged adenoids, although the inflammation had subsided and conservative treatment had ended. He had been exposed to screens since age one (background TV), started playing computer games with his father and brother three years prior, and had used a PlayStation for 30 minutes daily since the previous Christmas.

The youngest son, Simeon, aged 6, was described as irritable and restless. Before age 3, he had a distinct type of stuttering characterized by prolonged first syllables, facial grimacing, and unusual eye and head movements, which persisted for about a year. Unlike his brothers, he still took afternoon naps but tended to wake up in a bad mood, possibly due to poor sleep quality.

Two months prior to the evaluation, after the parents discovered educational videos from our Center, the family introduced strict screen restrictions. Boris’s screen use was limited to 30 minutes per day for short entertainment or sports videos. The two younger brothers followed a screen- and game-free daily routine. Notably, Simeon exhibited intense tantrums when screens were first removed, but his aggressive outbursts ceased completely after the new rules were implemented.

The interview with the mother, Sara, aged 40, was conducted in two parts. In the first, she focused on the children’s problems and stated that she had no personal health or emotional issues. She referred to marital difficulties that had occurred three years earlier but claimed they had been fully resolved through two years of psychotherapy, including joint family constellation work with her husband. She insisted they had since returned to being a “normal family.”

The father’s (Cain, aged 41) separate interview (unaware of what his wife had shared) offered a different perspective. He described in detail the events from three years earlier, including an affair with a colleague whom his wife also knew. At some point, he confessed to his wife about the relationship but said he could not choose between the two women. Before the confession, he and the other woman – who also had children – had made plans to live together. After the disclosure, he continued the affair while claiming not to want to destroy his family. Sara went through a severe emotional crisis that lasted six months. Their oldest son, Boris, was sent to live with the grandmother, and the household was filled with tension and arguments. The affair ended abruptly after the other woman’s husband found out – an encounter that likely involved violence. Since then, the two former lovers had avoided each other entirely.

The second part of the father’s interview revealed additional information following direct questions about addiction history. After firmly denying the use of alcohol, drugs, cigarettes, or gambling, he eventually disclosed difficulties in his sexual relationship with his wife. Before the affair, they had sex once a month, while he masturbated daily to pornography – a habit he had maintained since the age of 13. After the disclosure, they began having daily sexual relations, a pattern that continued at the time of the interview. His pornography use decreased to about 3–5 times per month. He had never spoken about this issue with a therapist or his wife.

qEEG and Autonomic Assessment

The Father (Cain, aged 41)

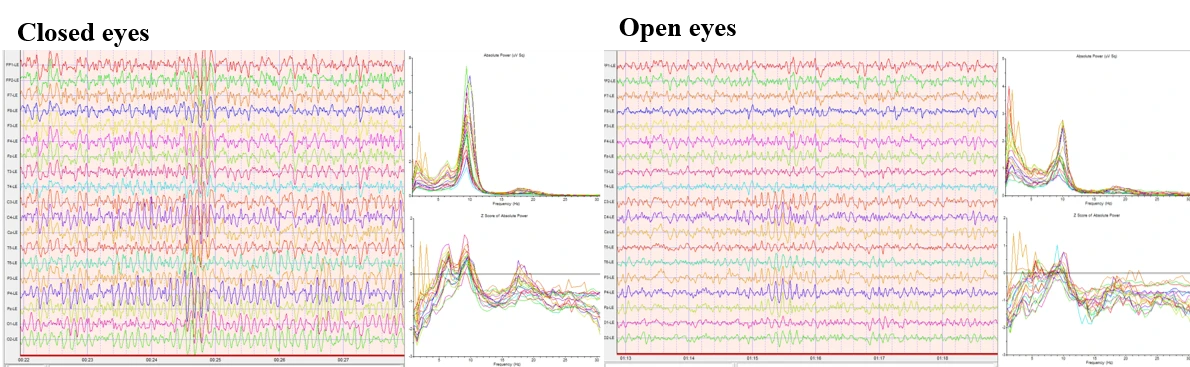

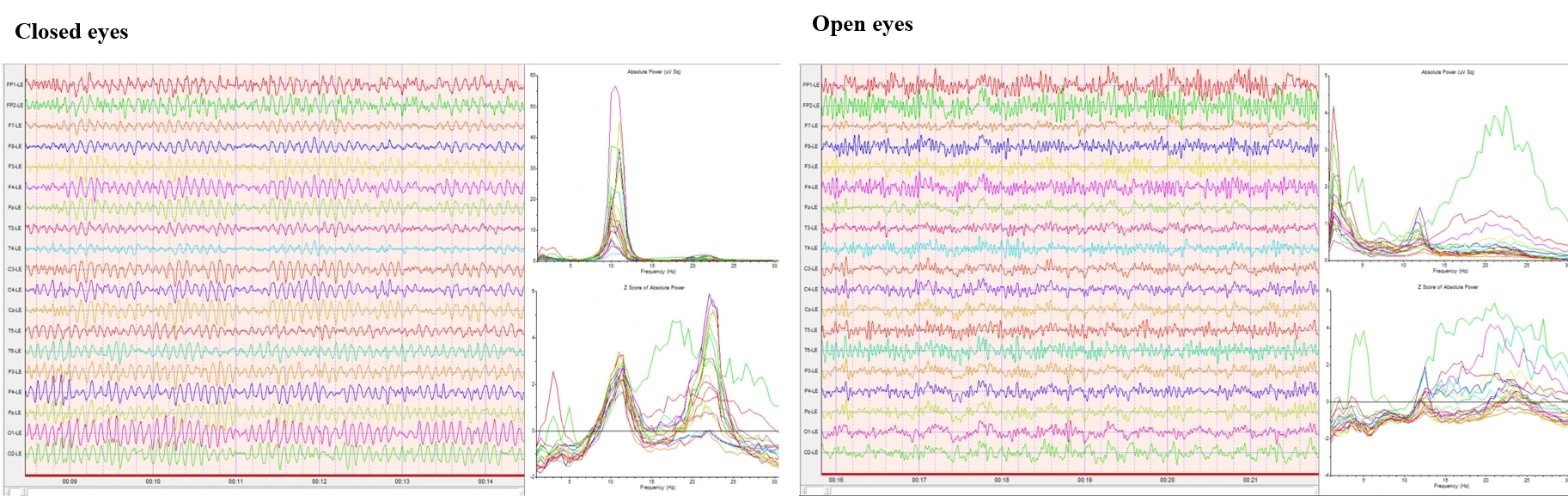

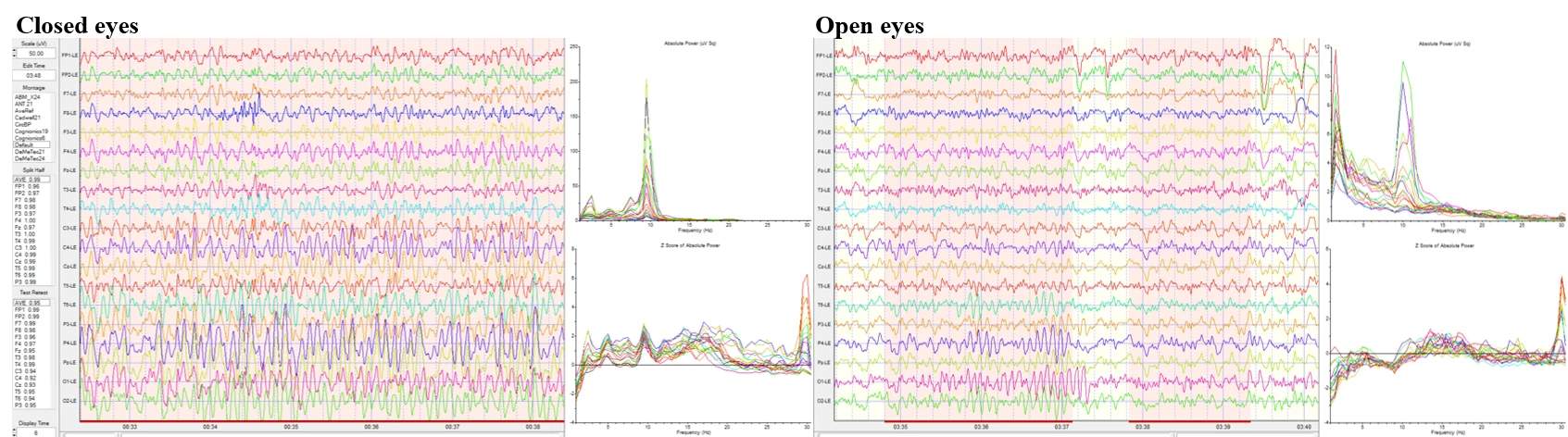

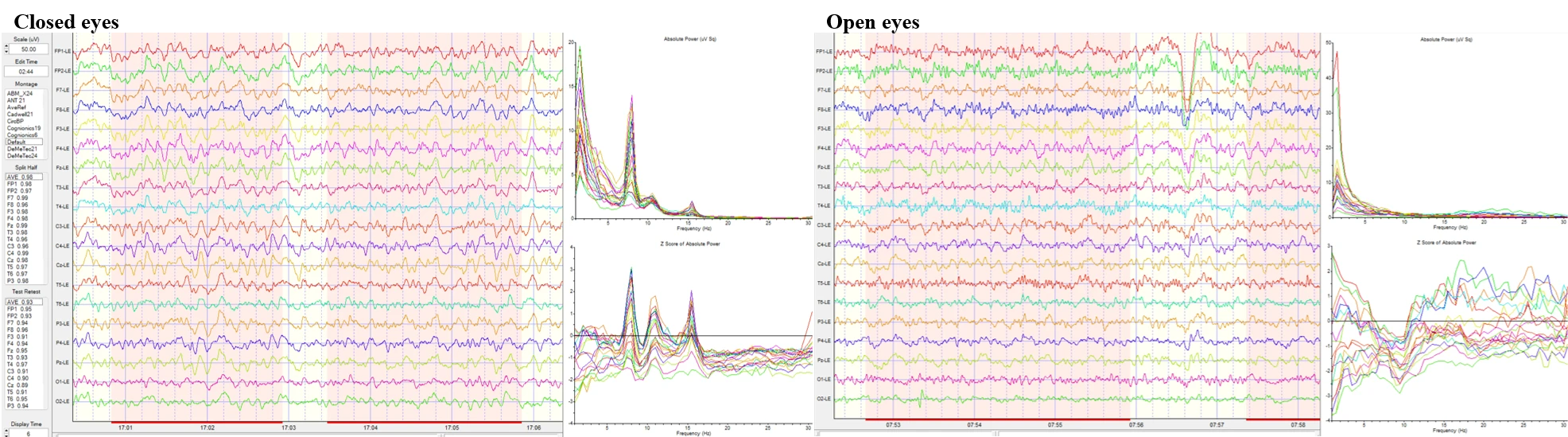

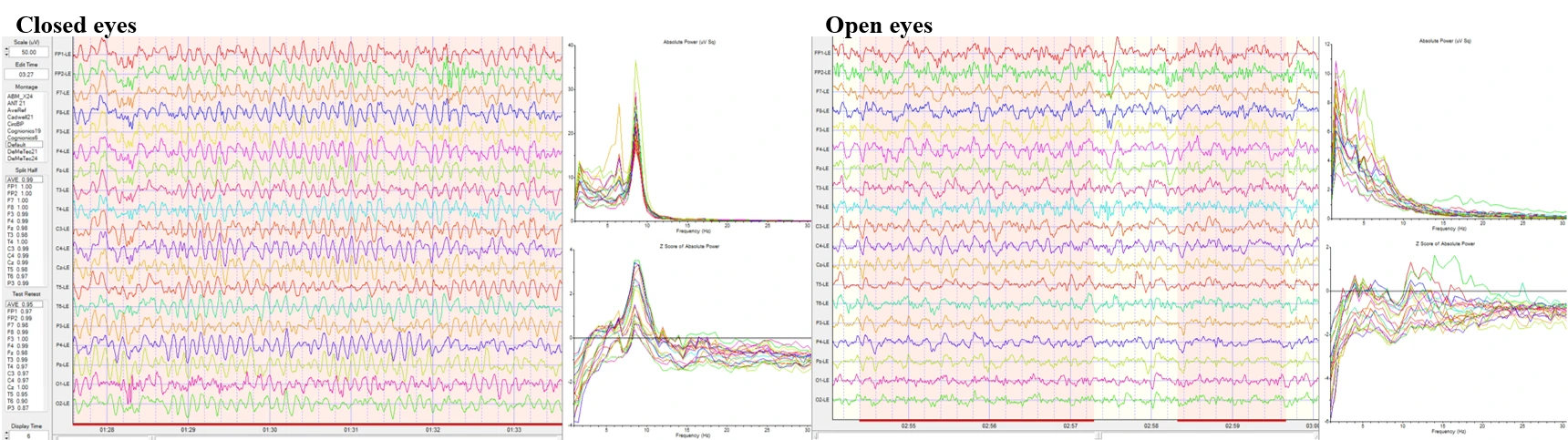

Figure 1-1 presents EEG data from Cain recorded under two conditions: eyes closed (left panels) and eyes open (right panels). For each condition, the top panel shows raw EEG traces from multiple scalp electrodes over time, revealing the general temporal structure and signal amplitude across channels. The middle panel displays the absolute power spectra, illustrating the distribution of signal power across frequency bands for all electrode sites. The bottom panel shows the corresponding Z-scores of absolute power, allowing for standardized comparison across frequencies and channels. This layout provides a comprehensive overview of the electrophysiological activity under both resting-state conditions.

Fig. 1-1. EEG Spectral Analysis of the Father Under Eyes-Closed and Eyes-Open Conditions. Raw EEG data (left), absolute power spectra (top right), and Z-scores of absolute power (bottom right).

Despite the presence of slow waves at 6.5 Hz and 9 Hz alongside the normal 10 Hz rhythm, comparison with the normative neurodatabase showed that all parameters remained within normal limits. The slow waves were visible only in the relative amplitude maps and corresponding indices, as shown in Fig. 1-2.

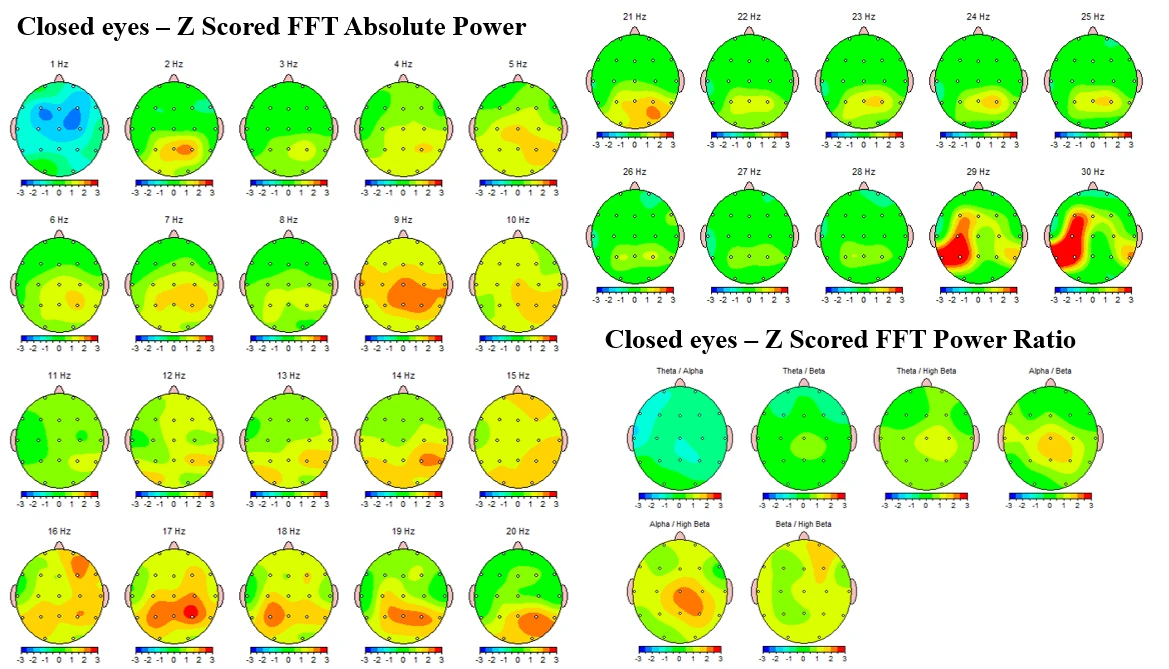

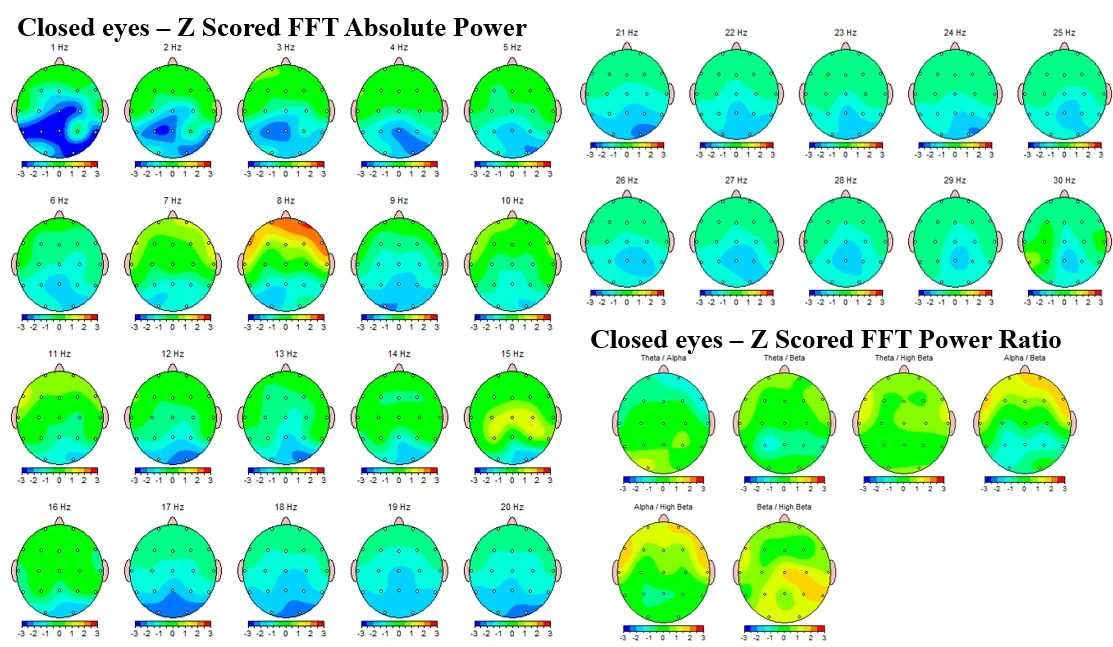

Figure 1-2 displays topographic Z-score maps of the father's EEG data across a range of frequencies and frequency band ratios. The upper portion of the figure shows a series of scalp maps from 1 Hz to 30 Hz, each representing the standardized power distribution at a specific frequency. Warmer colors indicate higher Z-scores, and cooler colors indicate lower values, relative to a normative database. The lower portion of the figure includes composite ratio maps for common clinical metrics, including theta/alpha, theta/beta, theta/high beta, alpha/beta, alpha/high beta, and beta/high beta. Each map provides a spatial overview of the brain’s relative power distributions and ratios across the scalp, with the goal of highlighting localized deviations from normative EEG patterns.

Fig. 1-2. Scalp topographies showing Z-scores of EEG absolute power across frequencies (1–30 Hz) and standard frequency band ratios (e.g., theta/alpha, alpha/beta) recorded during the eyes-closed condition in the father. The maps display deviations from a normative reference database, with color coding indicating standard score ranges.

Figure 1-3 shows EEG topographic Z-score maps of the father during the eyes-open condition. As in the previous figure, the upper portion presents absolute power distributions across the scalp from 1 Hz to 30 Hz, with each circular map representing a specific frequency.

Fig. 1-3. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Open Condition in the Father.

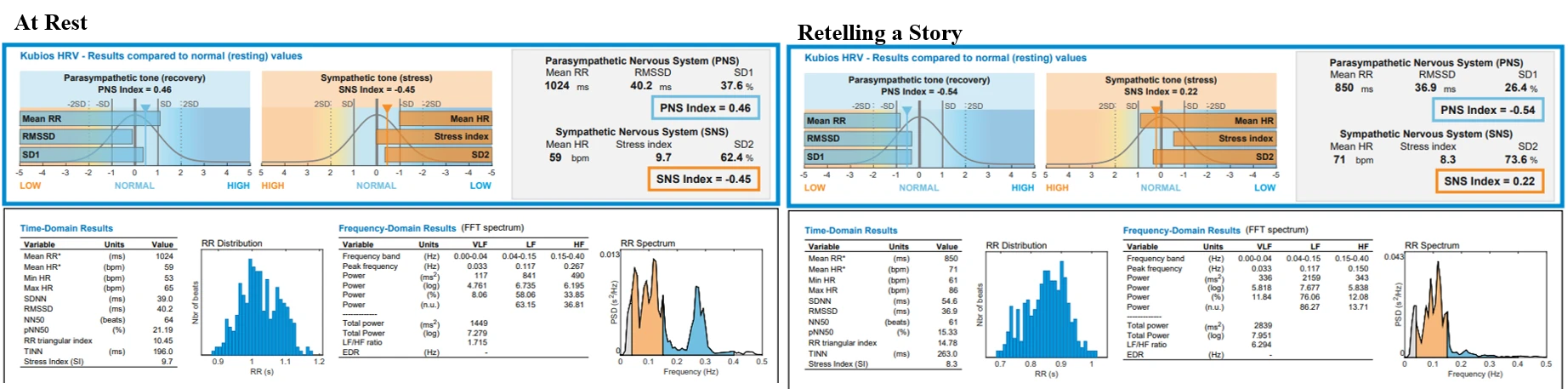

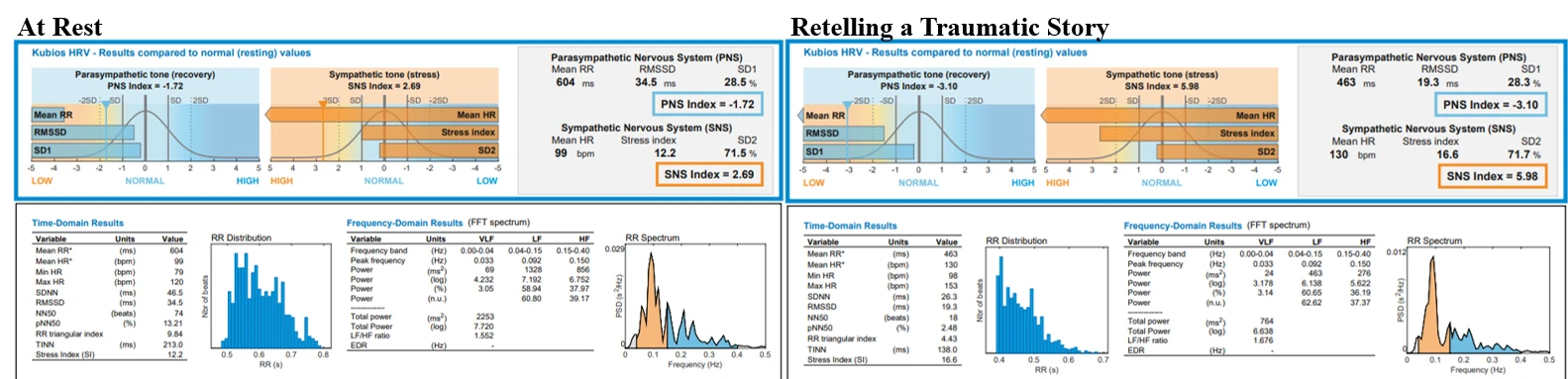

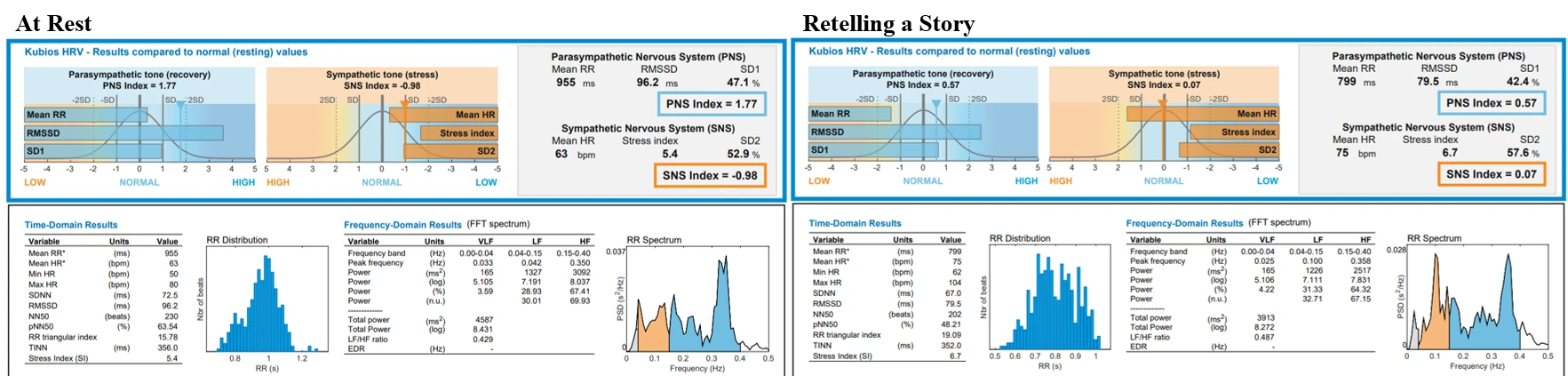

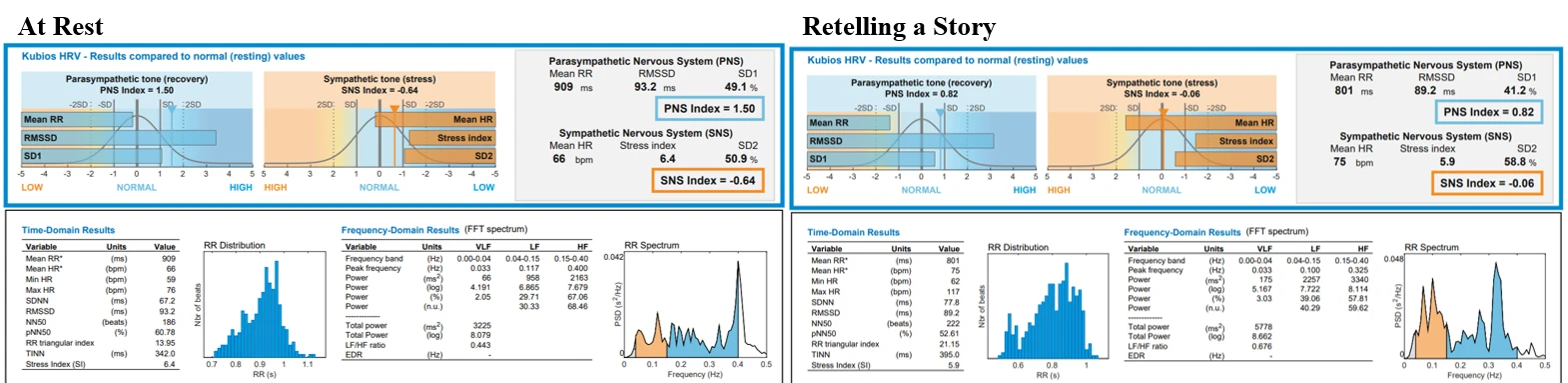

Figure 1-4 displays heart rate variability (HRV) data for father under two distinct conditions: resting baseline (left panel) and retelling of an emotionally significant story (right panel).

Fig 1-4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) of the Pornography-Addicted Father at Rest and During Emotional Retelling. RR (inter-beat interval), Mean RR (average of the inter-beat intervals), HR (heart rate), Mean HR (average heart rate), Min HR (minimum heart rate), Max HR (maximum heart rate), SDNN (standard deviation of NN intervals), RMSSD (root mean square of successive differences), NN50 (number of successive RR intervals differing by more than 50 ms), pNN50 (percentage of NN50 relative to total intervals), RR triangular index (geometric HRV measure), TINN (triangular interpolation of NN intervals), SI (stress index), VLF (very low frequency power, 0.00–0.04 Hz), LF (low frequency power, 0.04–0.15 Hz), HF (high frequency power, 0.15–0.40 Hz), TP (total power across all frequencies), LF/HF (low-to-high frequency power ratio), EDR (estimated respiration rate), PNS Index (parasympathetic nervous system index), SNS Index (sympathetic nervous system index)

Notably, the father's TINN value is higher at rest (196 ms) and lower during the emotionally engaging retelling condition (263 ms). This pattern is atypical, as TINN – a measure of overall heart rate variability – would normally be expected to decrease under stress or cognitive-emotional load and increase during restful states. The reversal observed here may suggest an altered or blunted autonomic response, possibly reflecting impaired parasympathetic modulation or emotional dysregulation often associated with chronic stress or behavioral addictions.

The Mother (Sara, aged 40)

Figure 2-1 presents EEG recordings from the mother under two conditions: eyes closed (left) and eyes open (right). In each condition, raw EEG traces from multiple scalp electrodes are shown in the top panel, providing a visual overview of temporal signal activity across regions. To the right of each trace set, spectral plots illustrate the absolute power across frequency bands (top right subpanel) and Z-scores of absolute power relative to normative data (bottom right subpanel). The eyes-closed condition shows a prominent peak in the alpha frequency range (~10 Hz), typical of resting-state activity, while the eyes-open condition is characterized by a reduction in alpha power and increased variability across higher frequencies. The Z-score plots visualize deviations from normative values, allowing for frequency-specific comparison between conditions and brain regions.

Fig 2-1. EEG Spectral Analysis of the Mother Under Eyes-Closed and Eyes-Open Conditions

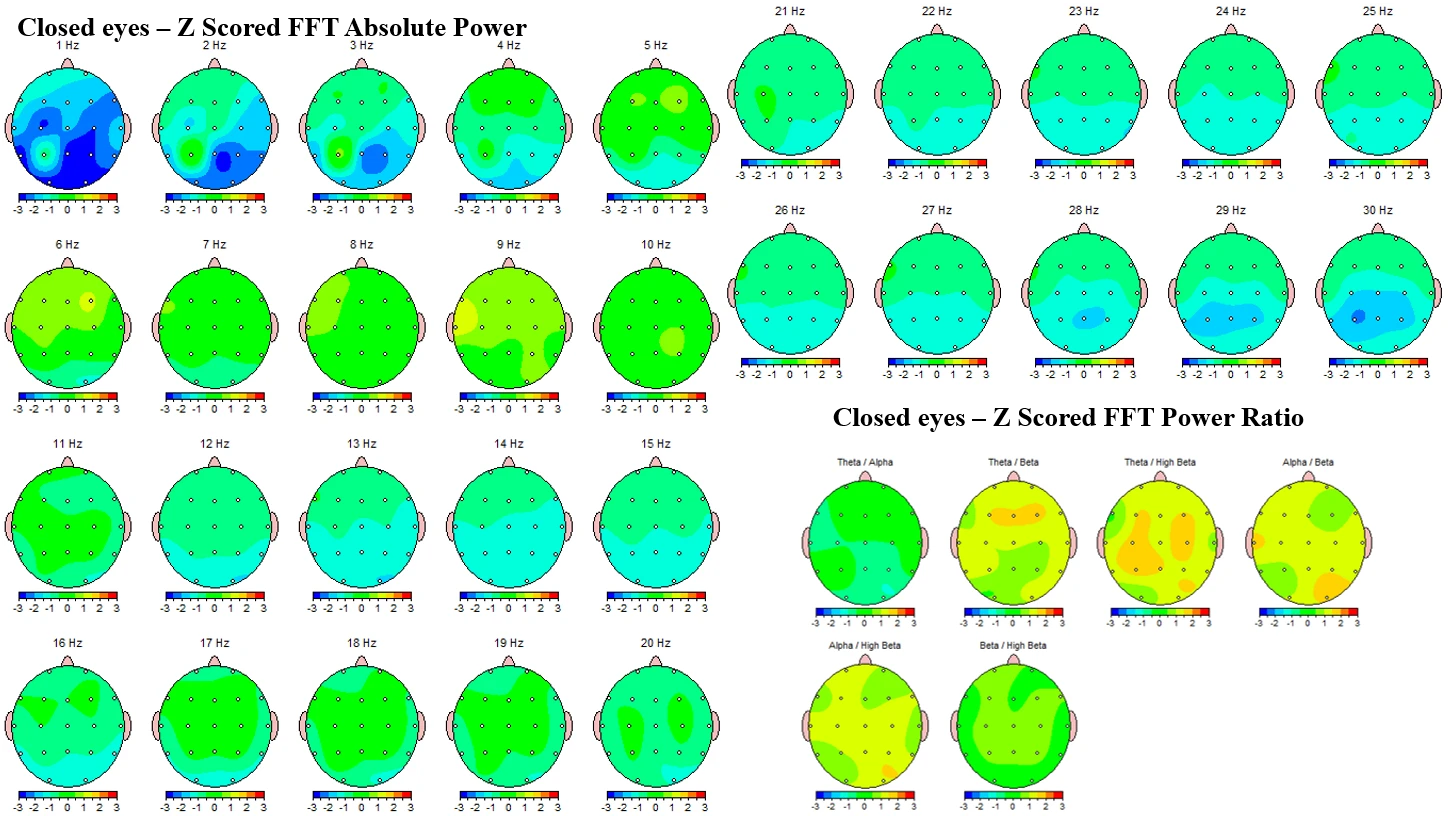

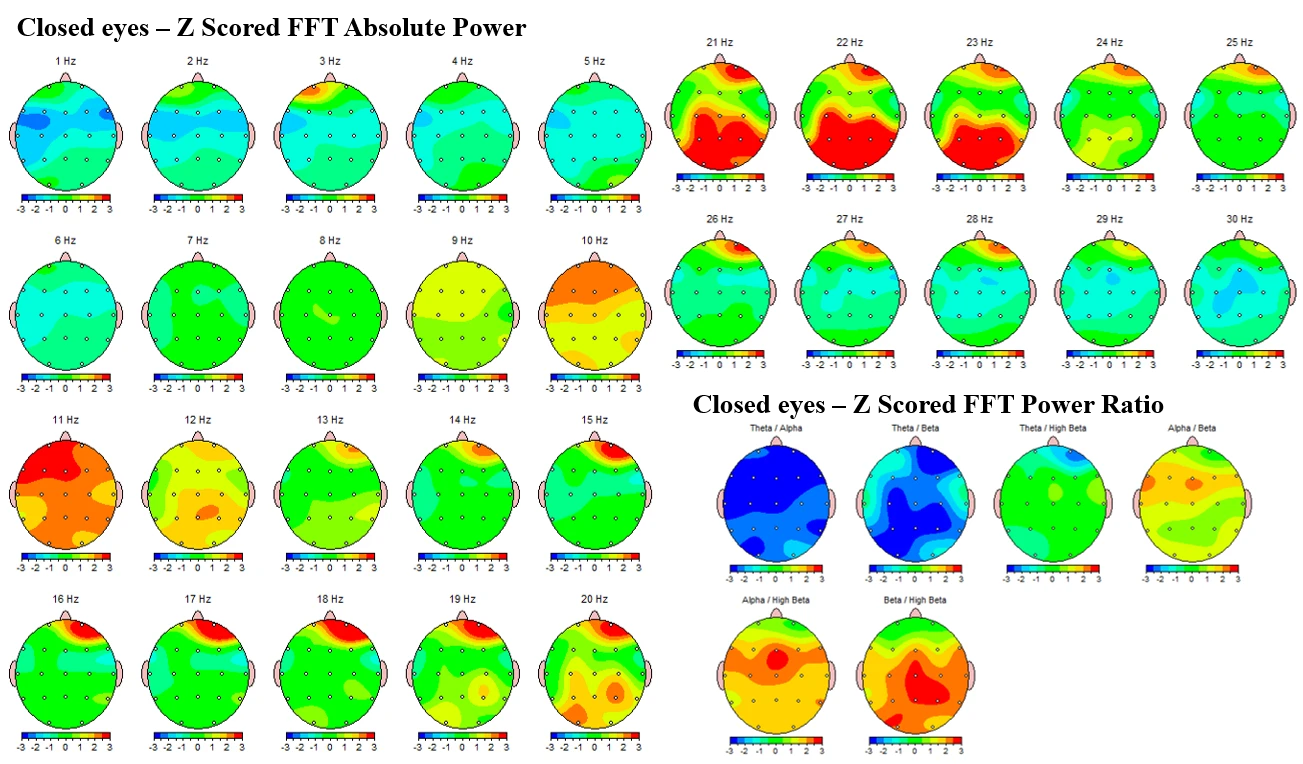

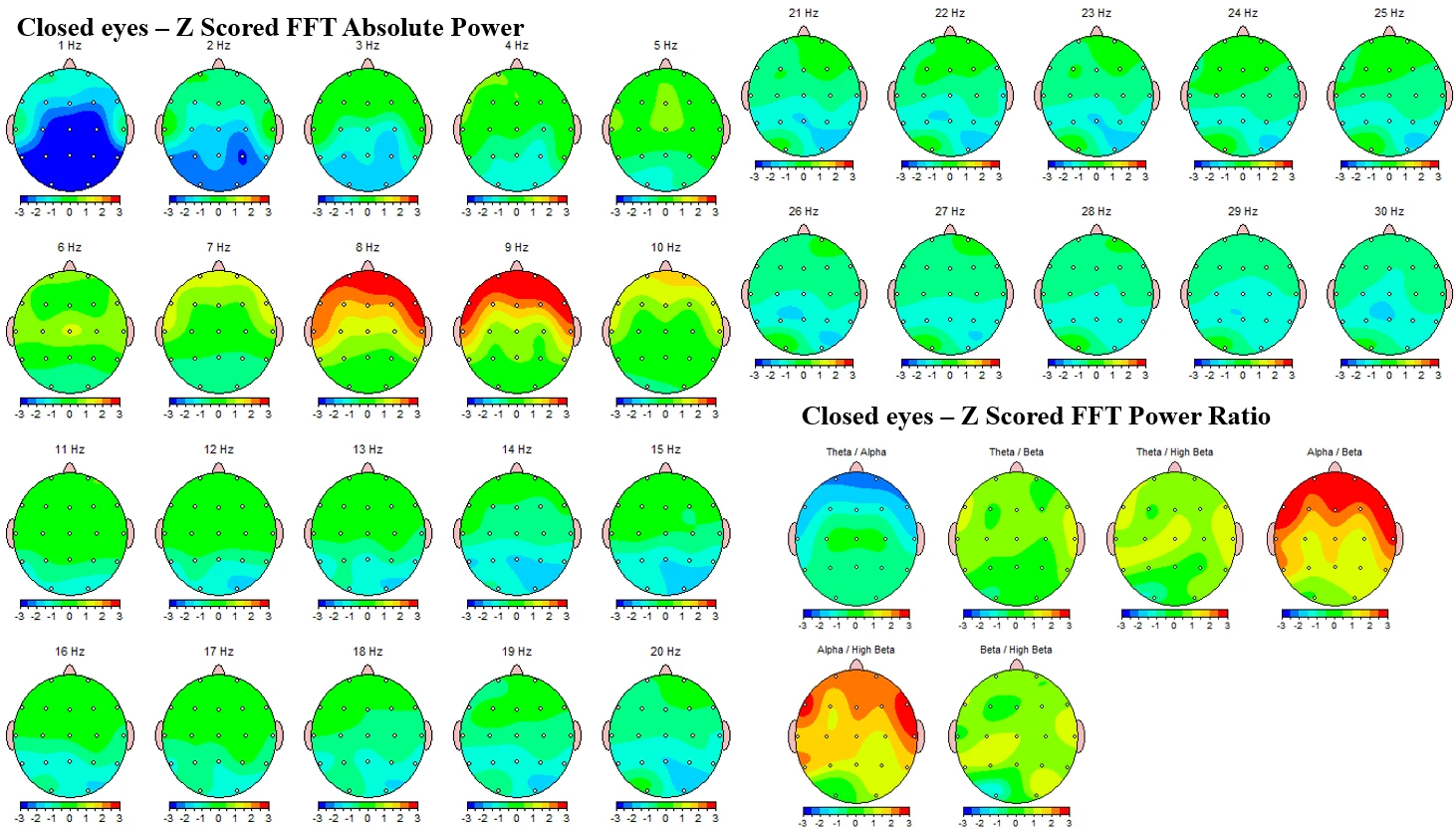

Figure 2-2 presents topographic maps of EEG Z-scores for the mother during the eyes-closed condition. The upper section of the figure shows 30 scalp maps corresponding to individual frequencies from 1 Hz to 30 Hz, each representing the standardized deviation in absolute power from a normative database. Elevated Z-scores were observed at 10 Hz over frontal regions, at 11 Hz globally across the scalp, and at 12 Hz predominantly in parietal areas during the eyes-closed condition.

Z-scores exceeding +3 were observed in the 20–23 Hz range over parietal and occipital recording sites, indicating markedly elevated activity in this high beta frequency band. Z-scores exceeding +2 were observed in the alpha/beta ratio over frontal regions, in the alpha/high beta ratio globally, and in the beta/high beta ratio across central, parietal, and occipital areas.

Fig 2-2. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Closed Condition in the Mother

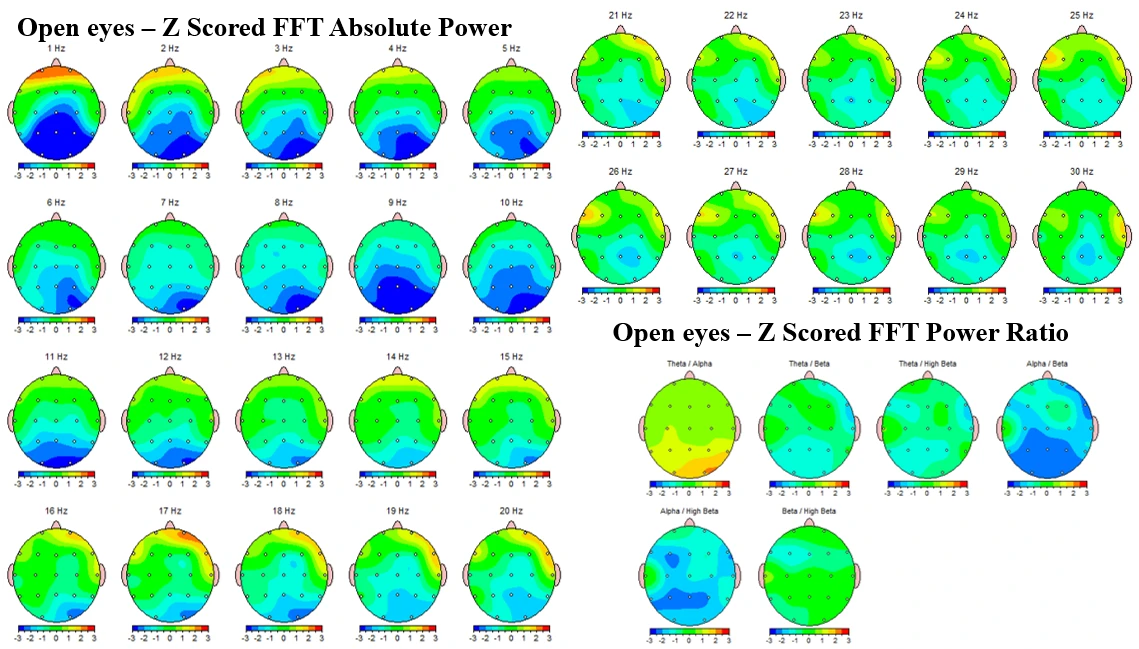

In the eyes-open condition (Fig. 2-3), the mother’s EEG shows several deviations from normative data. Notably, there are elevated Z-scores (≥ +2) in the beta (15-19 Hz) and high beta range (20–30 Hz) over Fp2 and F4, with some extension into T6. Additional increases above +2 are evident from 4 Hz to 5 Hz, particularly over O2. At the delta, theta and alpha frequencies, Z-scores are slightly decreased at 2-10 Hz, especially in the frontal and central regions. In the ratio maps, no significant elevations above +2 were observed, but mild deviations are present in the theta/beta, theta/high beta and alpha/high beta ratios, mainly in prefrontal and frontal zones.

Fig 2-3. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Open Condition in the Mother

Figure 2-4 presents heart rate variability (HRV) data for the mother, highlighting autonomic nervous system activity under two conditions: resting baseline (left) and emotional retelling (right). Both conditions show marked deviations from normative autonomic balance. In the resting condition (left), the mother exhibits a reduced parasympathetic tone (PNS Index = −1.72) and elevated sympathetic tone (SNS Index = +2.69), with a high stress index (12.2) and reduced RMSSD (30.4 ms). These values fall outside the typical range, indicating autonomic dysregulation even at rest. During the retelling condition (right), deviations are further pronounced, with severely suppressed parasympathetic activity (PNS Index = −3.10) and excessive sympathetic activation (SNS Index = +5.98), along with a high stress index (16.6) and a substantially elevated heart rate (130 bpm).

Fig 2-4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) of the Mother at Rest (Left) and During Emotional Retelling (Right)

These results reflect a strong physiological stress response with limited vagal recovery.

The oldest Son (Boris, aged 11)

Figure 3-1 shows EEG recordings from the oldest son (Boris) during eyes-closed (left) and eyes-open (right) conditions. In both conditions, raw EEG traces are displayed alongside spectral plots of absolute power and Z-scores. A typical alpha peak around 10 Hz is clearly present in the eyes-closed condition, indicating normal resting-state alpha rhythm. However, elevated absolute power is visible in the beta range (15-18 Hz) globally and in the high-frequency range (17-25 Hz), particularly over parietal and temporal sites, where Z-scores rise above normative levels. During the eyes-open condition, alpha activity diminishes as expected, but there is persistent elevated high-frequency activity in several channels.

Fig 3-1. EEG Spectral Analysis of the Oldest Son Under Eyes-Closed and Eyes-Open Conditions

These findings may reflect increased cortical arousal in Boris compared to typical age-matched norms.

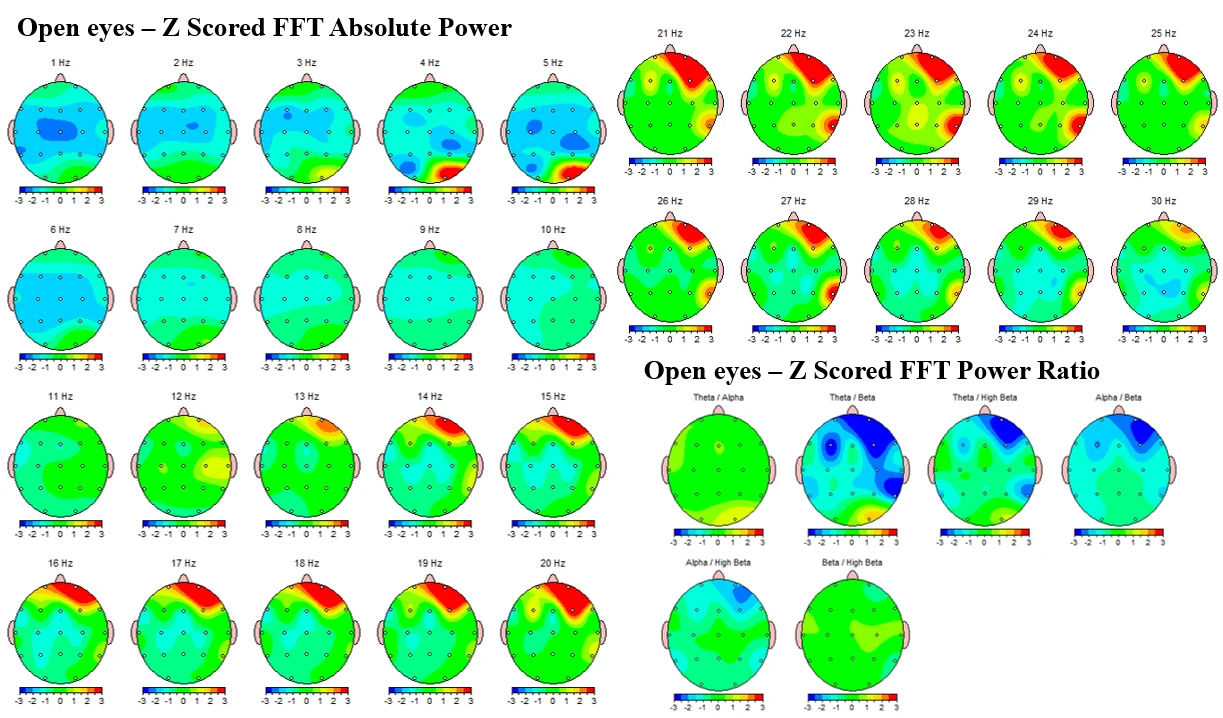

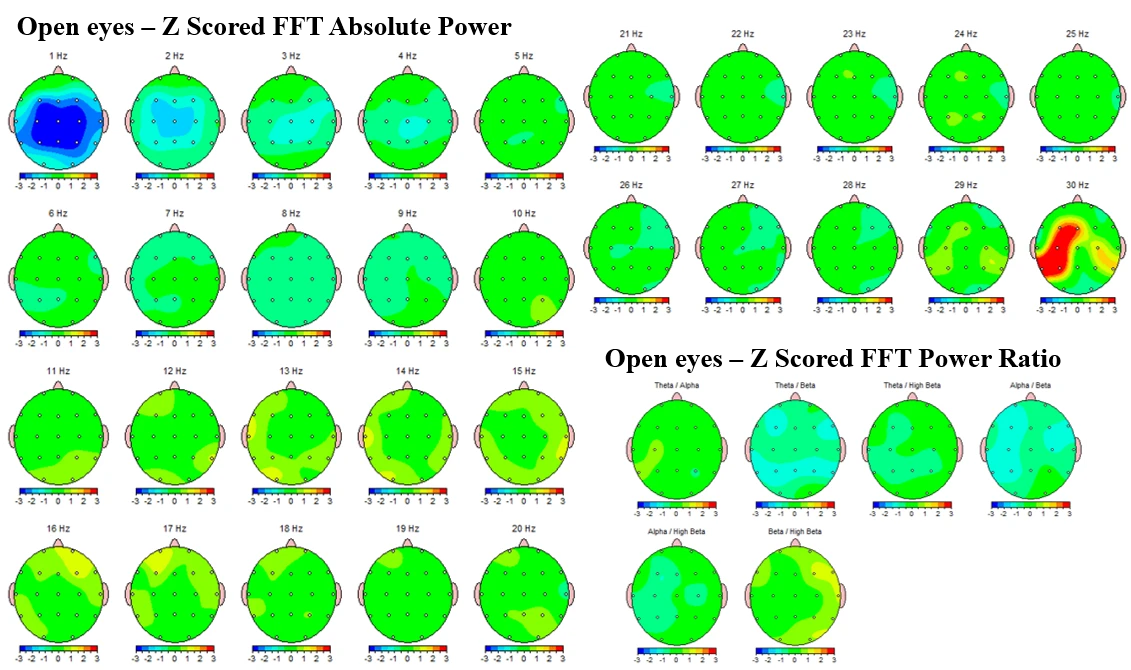

Figure 3-2 shows Z-score topographic maps for absolute EEG power across frequencies (1–30 Hz) and common band ratios during the eyes-closed condition in Boris. A typical alpha rhythm is observed, with slight elevations around 9–14 Hz across central and posterior regions. Notably, Z-scores exceed +2 at 9–10 Hz over centro-parietal areas and in the beta range (15–20 Hz), particularly frontally. The highest deviations are observed in the 30 Hz band, with Z-scores over +3 in posterior and lateral regions, indicating elevated high-frequency activity. In the ratio maps, alpha/beta, alpha/high beta and beta/high beta are mildly elevated (Z ≈ +2) over central and posterior areas, suggesting altered balance between inhibitory and excitatory activity in these regions.

Fig 3-2. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Closed Condition in the Oldest Son

Figure 3-3 displays topographic Z-score maps of EEG absolute power (1–30 Hz) and selected frequency band ratios for the oldest son (Boris) in the eyes-open condition. Overall, activity remains within normative limits across most frequency bands, with only minor deviations observed. A notable exception is a marked elevation in the 30 Hz band, where Z-scores exceed +3 over parietal and occipital regions, consistent with increased high beta/gamma activity. Band ratio maps show generally normative values, with only slight decrease in theta/beta, alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios, primarily in posterior and central regions. These findings suggest reduced resilience and an altered balance between inhibitory and excitatory activity in these regions during the eyes-open state.

Fig 3-3. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Open Condition in the Oldest Son

Figure 3-4 displays HRV parameters for Boris under resting conditions (left) and during emotional retelling (right). At rest, the data show a markedly elevated parasympathetic tone (PNS Index = +1.77) and a reduced sympathetic tone (SNS Index = −0.98), accompanied by a high RMSSD (96.2 ms), SDNN (72.5 ms), and low stress index (5.4), indicating strong vagal activity and low physiological arousal. During retelling, the parasympathetic activity decreases (PNS Index = +0.57), and sympathetic activity normalizes (SNS Index = +0.07), with a modest increase in the stress index (6.7) and decrease in RMSSD (55.2 ms).

Fig 3-4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) of the Oldest Son at Rest (Left) and During Emotional Retelling (Right).

The Second Son (Peter, aged 8)

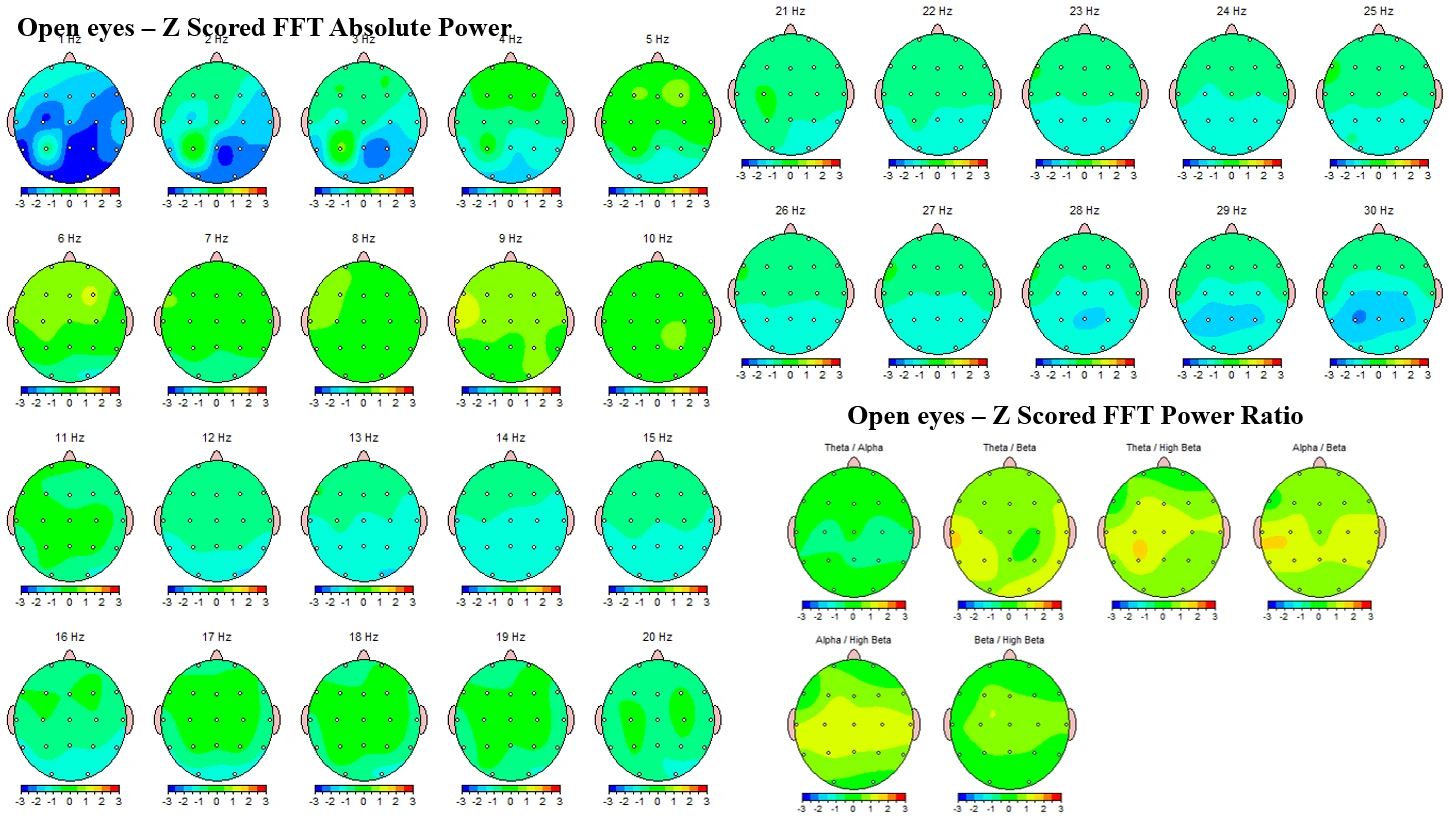

Figure 4-1 shows EEG recordings from the middle son (Peter) during eyes-closed (left) and eyes-open (right) conditions. Raw EEG traces from multiple scalp electrodes are displayed for each state, alongside spectral plots of absolute power and corresponding Z-scores. In the eyes-closed condition, a well-defined alpha peak around 10 Hz is visible in both power and Z-score plots, typical of resting-state EEG in children. Mild elevation in absolute power is also noted in the theta range (7,5 Hz) over frontal and central areas. During the eyes-open condition, alpha activity diminishes as expected, and the power spectrum shows a flatter profile with relatively higher beta-range activity, particularly above 15 Hz. The Z-score plot indicates moderate deviations above the normative range in high-frequency bands, consistent with increased cortical activation or arousal during eyes-open condition.

Fig 4-1. EEG Spectral Analysis of the Middle Son Under Eyes-Closed and Eyes-Open Conditions

Figure 4-2 displays EEG topographic Z-score maps for absolute power (1–30 Hz) and selected frequency band ratios in Peter during the eyes-closed condition. The most notable deviation is a Z-score elevation > +2 at 8 Hz, centered over frontal and central regions, indicating increased talpha activity. Additionally, mild decreases in the beta range (13–30 Hz) are observed posteriorly, with Z-scores approaching −2 in some posterior areas. In the ratio maps, alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios show elevations up to +2, particularly in frontal regions, while theta/alpha appears mildly reduced frontally. These deviations suggest a pattern of enhanced slow-to-intermediate frequency dominance, especially in the alpha range, with a relatively suppressed high-frequency component in posterior regions.

Fig 4-2. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Closed Condition in the Middle Son

Figure 4-3 presents EEG Z-score maps for absolute power across 1–30 Hz and selected frequency band ratios during the eyes-open condition in Peter. Compared to the eyes-closed state, there is a notable suppression of alpha activity (8–12 Hz), with Z-scores ranging from −1.5 to −3, especially over posterior regions, which is a typical response to visual engagement. Additionally, Z-scores below −2 are seen from 6–10 Hz, indicating a broad-band suppression of slow and low-alpha activity. In contrast, mild elevations (up to +2) in the beta range (17–20 Hz) appear over frontal and right parietal areas. The band ratio maps show decreased alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios, particularly in the posterior cortex, suggesting increased inhibitory tone and potential functional over arousal during the eyes-open condition.

Fig 4-3. Topographic Z-Score Maps of Absolute Power and Band Ratios During Eyes-Open Condition in the Middle Son

Figure 4-4 shows HRV data for Peter in two conditions: rest (left panel) and emotional retelling (right panel). In the resting condition, the child exhibits a high parasympathetic tone (PNS Index = +1.50) and low sympathetic tone (SNS Index = −0.64), reflected by elevated RMSSD (93.2 ms), SDNN (85.0 ms), and a low stress index (6.4). During emotional retelling, parasympathetic activity decreases (PNS Index = +0.82) but still remains high, and sympathetic tone increases slightly toward neutral (SNS Index = −0.06).

Fig 4-4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) of the Middle Son at Rest (Left) and During Emotional Retelling (Right)

The Third Son (Simeon, Aged 6)

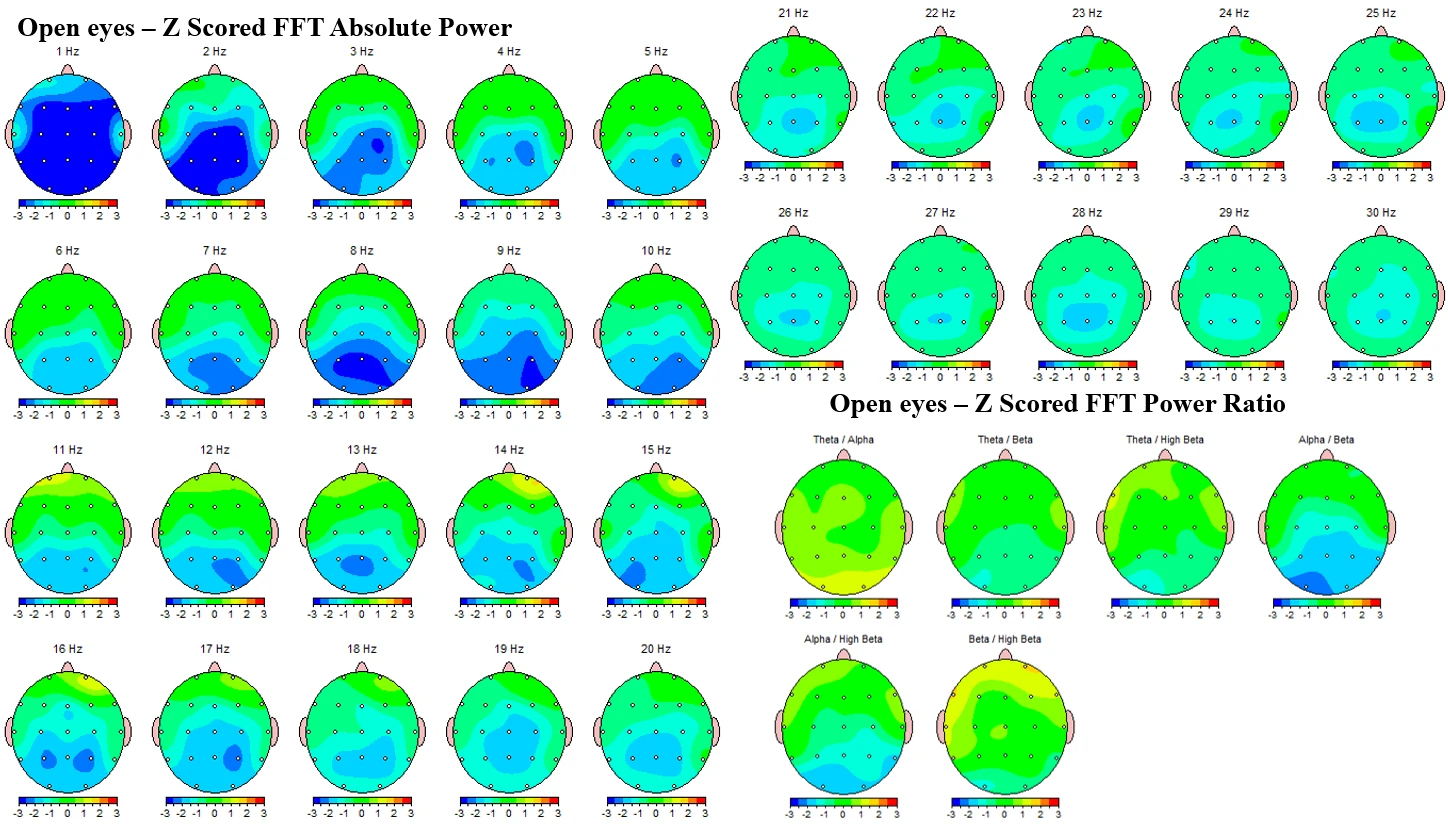

Figure 5-1 illustrates raw EEG traces, absolute power spectra, and corresponding Z-score deviations for the youngest son (Simeon) in two states: eyes closed (left panel) and eyes open (right panel). The eyes-closed condition shows dominant occipital alpha activity peaking near 8,5-9,0 Hz, typical for resting-state neural rhythms at this age. During eyes-open recording, overall amplitude decreases as expected, but a less distinct alpha peak and irregular spectral elevation in low beta frequencies is visible.

Fig 5-1. EEG Recordings of the Youngest Son During Eyes-Closed (Left) and Eyes-Open (Right) Conditions

Figure 5-2 presents topographic Z-score maps of absolute power (1–30 Hz) and key frequency band ratios for the youngest son (Simeon). The most pronounced deviations include elevated 8–10 Hz alpha power exceeding +3 Z in prefrontal and frontal regions, consistent with strong resting-state alpha. Additionally, theta/alpha and theta/beta ratios remain within normative limits, whereas alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios are markedly increased across frontal and temporal regions, reflecting lack of cortical inhibition.

Fig 5-2. Z-Scored Absolute EEG Power and Band Ratios in the Youngest Son

The maps in Fig. 5-3 reveal a marked reduction in absolute power over posterior regions at −3 Z-scores in the 1–10 Hz range, and a moderate reduction in parietal regions at −2 Z-scores in the 12–20 Hz range. Additionally, both the alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios are decreased by approximately −2 Z-scores over parietal and occipital sites.

Fig 5-3. Z-score topographic maps of EEG frequency bands and band ratios for the youngest son, eyes open.

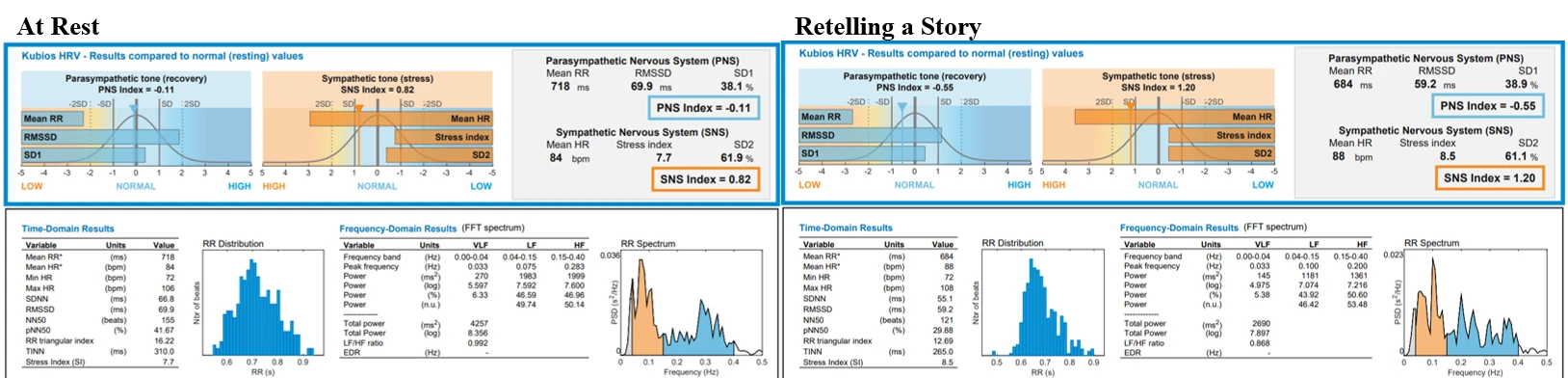

Figure 5-4 illustrates heart rate variability (HRV) parameters at rest (left panel) and during story retelling (right panel) in the youngest son (Simeon). At rest, the HRV profile shows a slightly reduced parasympathetic tone (PNS index = –0.11) alongside a mildly elevated sympathetic tone (SNS index = 0.82), suggesting a state of physiological alertness. During story retelling, a further reduction in parasympathetic activity is observed (PNS index = –0.55), accompanied by a pronounced increase in sympathetic activation (SNS index = 1.20)

Fig. 5-4. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) of the Youngest Son at Rest (Left) and During Emotional Retelling (Right)

Discussion

The story of a seemingly peaceful family bed, which suddenly and irreversibly changes due to Cain's affair, is only the surface layer. The hidden family dynamics once again determine the relationships and, most importantly, the health of the children (Petrov et al., 2025). The psychological trauma inflicted by the father on all other family members is profound, but it does not fully explain the overall dynamic.

What we observe here is the opposite of the widely accepted notion that trauma precedes all forms of addiction (Maté, 2008; 2012; Levine, 2010; 2015; Maté & Maté, 2022). In our clinical practice, as in this case, we often find that addictive and traumatic functioning are closely intertwined – often indistinguishable. Trauma and addiction appear as two sides of the same coin, mutually reinforcing each other.

Particularly revealing is Cain’s long-term behavioral addiction, which began in early adolescence and has shaped all his life decisions, especially those involving relationships with women. The fact that he engaged in sexual intercourse with his wife only once a month, while masturbating to pornography daily, clearly indicates that the relationship was not fulfilling from the beginning. He kept this hidden – his wife had no knowledge of his addiction – a pattern typical for those struggling with addiction.

Interestingly, Cain initiated the affair six months before he confessed it to his wife, although he told her it had only lasted three months. Lying or withholding the full truth is a commonly used strategy in the repertoire of individuals with addictions. One might ask: why did Cain choose to confess at all? For three months, the drama of indecision unfolded – he maintained both relationships without making a choice. In the end, the affair did not conclude through a decision made by either Cain or his mistress, but through the intervention of the other woman's husband – likely involving violence. The resolution was imposed by someone else, and both Cain and his mistress passively accepted it as their "fate."

Beneath the surface, something entirely different is revealed. The abulia (lack of will) displayed by both parties is characteristic of addictive functioning. The urge to harm oneself or one's partner is evident. If Cain truly cared for the other woman, he would have done everything possible to separate from his wife – but he did not. What’s more, in an effort to keep him, his wife began having sex with him daily, regardless of how she felt emotionally – and he agreed. Such dissociation is characteristic of traumatic functioning and the assumption of the victim role.

As seen in this case, Cain’s addiction became stabilized through Sarah’s trauma-based behavior, and the couple continued their life together.

If the other woman had not been part of Cain’s addiction but had instead been involved in a genuinely committed relationship with him, she likely would not have submitted to her husband after being discovered. Likewise, Cain would not have abruptly stopped seeking her – perhaps out of fear of complications. But regardless of the reasons Cain gave for his behavior, his unconscious motives can be inferred from the outcome. Specifically, he succeeded in making his wife co-addicted. He did so in a particularly manipulative way – by confessing the affair without being willing to make a decision. He was fully aware that Sarah was unemployed and entirely dependent on him – financially and socially – as he was the family’s sole provider. With three children to care for, it would have been extremely difficult for her to end the relationship upon discovering the truth. Ultimately, Cain got what he wanted: daily sexual gratification, effectively replacing pornography with his wife.

His psychophysiological functioning appeared relatively normal (see Figs. 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-4), with a low baseline level of arousal, characteristic of addictive and depressive profiles. Only on rare occasions – such as while recounting the affair – did slow-wave activity and sympathetic arousal emerge (data not shown).

Sarah, by contrast, showed the opposite pattern. Her baseline was marked by elevated anxiety, interspersed with freezing reactions during the narration of their “family issues”. She was severely traumatized, yet chose to continue the relationship "for the sake of the children," holding onto hope that the broken bond could be repaired. Even after two years of therapy, she remained in denial, convincing herself that things had improved – without recognizing that she had become a hostage to her husband’s addiction.

At the same time, she was acutely aware that she had gained control over her husband, believing he would no longer be unfaithful. Power, not love, had come to define their toxic dynamic. This power struggle escalated to the point that, six months before the evaluation, Cain left his high-paying job and embarked on a risky business venture with Sarah’s brother, gradually depleting the family’s savings. His risky behavior and trauma-prone tendencies persisted – only now redirected into a business context.

Sarah’s overall functioning was marked by trauma-driven, anxious-depressive dynamics and pronounced sympathetic overactivation, alternating with classic freezing responses during the recall of traumatic events (see Figs. 2-1, 2-2, 2-3, 2-4).

The children’s responses to the events in the family provide important insights. All three sons exhibited mild to moderate levels of screen addiction and mild to moderate screen-induced trauma. The increased use of shared computer games coincided with the onset of the marital crisis, beginning more intensely around three years prior.

The youngest son developed stuttering and tic-like movements shortly after his father initiated the extramarital affair – approximately six months before the disclosure to the mother – suggesting an early, unconscious sensitivity to family tension. The middle son responded with stuttering and a traumatic arm fracture, which occurred during a period when the mother was in acute psychological shock, reflecting a strong somatic link to her emotional state. The eldest son, Boris, acted as a kind of proxy or enabler for his father, systematically dominating and intimidating his younger siblings, while fully internalizing the father’s addictive behavioral model.

Notably, Boris somehow succeeded – despite being the most affected by screen addiction and gaming, and exhibiting pronounced attention deficit and learning difficulties (Stefanova et al., 2025) – in negotiating 30 minutes of daily screen time for himself. This contradiction is telling. The tolerance of screen addiction by addicted fathers is not an uncommon phenomenon (Vezenkov & Manolova, 2025(1)). Cain’s baseline state alternated between freezing reactions and third-degree psychophysiological tension, especially when discussing the affair and his addiction. His low-arousal, dissociated functioning was mirrored by his two older sons – but not the youngest.

Sarah, in contrast, demonstrated a high baseline level of autonomic arousal, alternating with strong freezing responses while recounting the affair or discussing her sons. This pattern is consistent with chronic trauma and co-addicted functioning. Her very low resilience, chronic fatigue, and anxious-depressive psychophysiology correlated with an insecure attachment style, which appeared to strongly influence the emotional regulation and development of the younger sons (Petkova et al., 2025).

In Boris (age 11), there were clear signs of screen trauma (Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025(2)) as well as typical indicators of screen addiction (Vezenkov & Manolova, 2025(2)). His freezing responses (data not shown) closely mirrored those of his father. Neurophysiologically, he displayed classic alpha-theta fusion patterns – a hallmark of screen trauma. While such patterns were only occasionally present in Cain, they were more pronounced and consistent in Boris, suggesting a consolidated pattern of addictive and trauma-based functioning (see Figs. 3-1, 3-2, 3-3, 3-4). His stuttering lasted for about one year, emerging immediately after his mother’s emotional collapse, but later resolved. His trauma later manifested more in the form of severe attentional deficits and narcissistic, automatized behavior.

Peter (age 8) exhibited not only freezing responses (Fig. 4-4), but also a somatization of trauma, with two arm fractures – one of which occurred during an altercation with his brother Boris. In the absence of traumatic functioning, such a fracture would have been unlikely from a typical physical collision during football. Here, a freeze reaction and motor block clearly contributed to the severity of the injury. According to the father, who witnessed the incident, it was “unbelievable” that such a mild push could result in multiple fractures. In addition, Peter exhibited a severe fluency disorder – stuttering – on an executive level, without any apparent cognitive impairment (see Figs. 4-1, 4-2, 4-3). As noted earlier, screen addiction can lead to neurological, not only psychological, impairments (Vezenkov & Manolova, 2025(2)).

In the case of the youngest son, Simeon, the neurophysiological and HRV findings support the clinical observation of his relatively rapid recovery following full screen detox, as mentioned in the text. Despite his history of transient stuttering at the onset of his father’s affair, which resolved quickly, the QEEG (Figs. 5-1 to 5-3) still shows subtle traces of screen-related trauma. Specifically, Fig. 5-2 reveals increased alpha/beta and alpha/high beta ratios in parietal and occipital areas (–2 Z), suggesting residual cortical hypoarousal patterns often linked to past overstimulation. In Fig. 5-3, a widespread reduction of absolute power in the 1–10 Hz range (–3 Z posteriorly, –2 Z parietally) indicates lingering dysregulation of low-frequency rhythms despite overall normalization. Interestingly, the HRV data (Fig. 5-4) shows a markedly elevated SNS index during the storytelling task (SNS index = 1.20), reflecting high sympathetic arousal under stress, alongside a decrease in PNS index compared to baseline. This pattern suggests that while his baseline functioning may appear normalized, Simeon remains physiologically sensitive to emotionally charged stimuli. These findings highlight the long-term imprint of early relational and digital trauma, even in children showing rapid behavioral recovery.

A confirmation that the trauma-addiction dynamic was both mutually desired and stabilized by the parents is the fact that the family did not proceed with therapy after the initial assessment – despite initially expressed enthusiasm (Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025(2)). During the first evaluation, several deep and painful truths about the hidden family dynamics emerged, even though the parents initially focused exclusively on their children's problems. The pattern of seeking help only to reject it when it becomes truly effective is a phenomenon frequently observed in our clinical practice (Manolova et al., 2025).

Conclusion

This family case study highlights the intricate interplay between unresolved parental trauma, behavioral addiction, and child neurodevelopment. The father’s long-standing pornography addiction and emotional detachment created a cascade of dysfunction that deeply impacted the psychological and neurophysiological health of all three children. The mother’s trauma response, marked by chronic anxiety, depressive functioning, and co-addiction, further reinforced the toxic family dynamic.

Neurophysiological assessments revealed distinct patterns in each family member, corresponding to their unique roles and reactions within the family system. While the father’s flattened autonomic reactivity and dissociative baseline reflected his addictive profile, the mother displayed a hyperaroused stress system alternating with parasympathetic shutdown – typical of trauma survivors. The children, in turn, demonstrated various degrees of screen addiction, trauma symptoms, and functional impairment, closely mirroring the unresolved issues of their parents.

Our findings emphasize that screen addiction -related dysfunctions in children – such as attention deficits, stuttering, aggression, and emotional dysregulation – should not be viewed in isolation but rather as embedded within broader intergenerational patterns of addiction and trauma. Importantly, the youngest child’s rapid recovery following screen detox suggests that early intervention can be effective, though deeper trauma markers may persist.

The case underscores the need for systemic, family-centered approaches in both diagnosis and intervention. Behavioral addictions like problematic pornography use may remain hidden but can exert long-term effects on partners, parenting, and children’s development. Multimodal assessment – including neurophysiological data – can help reveal hidden dynamics and guide targeted interventions aimed at breaking cycles of co-addiction and dysfunction across generations. Moreover, the family's refusal to begin therapy after the initial evaluation – despite initial motivation – further illustrates how trauma-addiction systems can become self-reinforcing and resistant to change, even in the face of insight and professional support.

References

Alexandrov, I.I, Manolova, V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Infantile Behavior Patterns and Developmental Delays in Adolescents and Young Adults (Aged 12-29) with Screen Addiction. Nootism 1(1), 79-82. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.8

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., and Potenza, M. N. (2019). The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Chen, L., Jiang, X., Wang, Q., Bőthe, B., Potenza, Marc. N., and Wu, H. (2021). The Association between the Quantity and Severity of Pornography Use: A Meta-analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(6), 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1988500

Duffy, A., Dawson, D. L., and das Nair, R. (2016). Pornography addiction in adults: A systematic review of definitions and reported impact. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(5), 760–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.002

Kühn, S., and Gallinat, J. (2014). Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: The brain on porn. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(7), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.93

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. A. (2015). Trauma and memory: Brain and body in a search for the living past: A practical guide for understanding and working with traumatic memory. North Atlantic Books.

Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Parental Models: A Profile of the Dynamics in Children Dropping Out of Therapy Programs for Screen Addiction. Nootism 1(1), 96-100. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.11 (1)

Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Screen Trauma – Specifics of the Disorder and Therapy in Adults and Children. Nootism 1(1), 37-51. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.3 (2)

Marshall, E. A., and Miller, H. A. (2019). Consistently inconsistent: A systematic review of the measurement of pornography use. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 169-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.019

Maté, G. (2008). In the realm of hungry ghosts: Close encounters with addiction. Knopf Canada.

Maté, G. (2012). Addiction: Childhood Trauma, Stress and the Biology of Addiction. Journal of Restorative Medicine, 1, 57–77. https://doi.org/10.14200/jrm.2012.1.1005

Maté, G., and Maté, D. (2022). The myth of normal: Trauma, illness, and healing in a toxic culture. Avery.

Mestre-Bach, G., and Potenza, M. N. (2023). Pornography use, problematic pornography use, and potential impacts on partners and relationships. Current Addiction Reports, 10, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-023-00468-5

Mestre-Bach, G., and Potenza, M. N. (2024). Inhibitory control in gambling disorder, internet gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behavior disorder/problematic pornography use: A review of the last 5 years. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 11(2), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-024-00272-z

Mestre-Bach, G., and Potenza, M. N. (2025). Adolescents, Pornography Use, and Problematic Pornography Use: A Rapid Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.5765/jkacap.250015

Mestre-Bach, G., Blycker, G. R., and Potenza, M. N. (2020). Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 181-183. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00015

Mestre-Bach, G. and Potenza, M.N. (2023) Loneliness, Pornography Use, Problematic Pornography Use, and Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Curr Addict Rep 10, 664–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-023-00516-0

Pashina I.H., Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Parental Recovery as a Key Factor for the Recovery of Children with Screen Addiction – Biofeedback Therapy for Severe Disorders. Nootism 1(1), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.9

Petkova, S. P., Manolova, V. R., and Vezenkov, S. R. (2025). Restoring attachment in children with early screen addiction. Nootism 1(1), 74-78. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.7

Petrov P.P., Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Hidden Family Dynamics in a Case Study of a Child with Screen Addiction, Hyperactivity, and Language Deficits. Nootism 1(1), 90-95. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.10

Potenza, M. N. (2018). Pornography in the current digital technology environment: An overview of a special issue on pornography. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2019.1567411

Seyedzadeh Dalooyi, S. I., Aghamohammadian Sharbaaf, H., Abdekhodaei, M. S., and Ghanaei Chamanabad, A. (2023). Biopsychosocial Determinants of Problematic Pornography Use: A Systematic Review. Addiction & health, 15(3), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.34172/ahj.2023.1395

Stark, R., Klucken, T., Potenza, M. N., Brand, M., and Strahler, J. (2018). A current understanding of the behavioral neuroscience of compulsive sexual behavior disorder and problematic pornography use. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 5(4), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-018-0162-9

Stefanova M.Ts., Manolova, V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) ADHD and Screen Addiction in Children Aged 3-9: Staged Recovery and Neurophysiological Markers. Nootism 1(1), 66-73. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.6

Straub, J., and Schmidt, C. (2022). A Period of Abstinence from Masturbation and Pornography Leads to Lower Fatigue and Various Other Benefits: A Quantitative Study. Journal of Addiction Science, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.17756/jas.2021-056

Vezenkov, S. R., and Manolova, V. R. (2024). A Central Role of Biofeedback in a Complex Therapy of Screen Devices Usage Addiction. BFE 21tst Meeting Montesilvano, Italy, 21-22 September 2022, In APPLIED PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY AND BIOFEEDBACK. Vol. 49, No. 1, 173-173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-023-09607-0

Vezenkov, S.R. and Manolova, V.R. (2024) Rethinking Autism: The Screen Addiction Paradigm. BFE 22nd Meeting, 8-13 April 2024, Ljubljana, Slovenia, doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27970.80328

Vezenkov, S.R. and Manolova, V.R. (2025) Gaming and Gambling Addiction in Fathers as a Risk Factor for Early Screen Addiction in Children. Nootism 1(2), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.2.3 (1)

Vezenkov, S.R. and Manolova, V.R. (2025) Screen Addiction – Biomarkers, Developmental Damage and Recovery. Nootism 1(1), 6-18. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.1 (2)

Vezenkov, S.R. and Manolova V.R. (2025) Neurobiology of Autism/Early Screen Addiction Recovery. Nootism 1(1), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.2 (3)

Vieira, C., and Griffiths, M. D. (2024). Problematic Pornography Use and Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 31(3), 207–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/26929953.2024.2348624

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.).