Violeta R. Manolova and Stoyan R. Vezenkov

Center for applied neuroscience Vezenkov, BG-1582 Sofia, e-mail: info@vezenkov.com

For citation: Manolova V.R. and Vezenkov S.R. (2025) Chronic Intimate Partner Violence, Autonomic Dysregulation, and Intergenerational Impact: A Case Study with HRV Analysis. Nootism 1(5), 35-43, https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.5.3

Abstract

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) represents one of the most persistent and devastating psychosocial stressors, with implications that extend beyond the psychological to measurable physiological dysregulation. This article presents a detailed clinical case of a 38-year-old woman subjected to 20 years of systematic physical and sexual violence, alongside caregiving for two children with neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders. Using heart rate variability (HRV) as an objective biomarker, the study demonstrates converging reductions in RMSSD and HF with elevated LF/HF, consistent with reduced vagal modulation and heightened arousal linked to trauma-related dysregulation.

Drawing on contemporary trauma theory and psychophysiological research, we conceptualize IPV as a pathological dyadic homeostasis in which the perpetrator’s aggression operates as a behavioral addiction while the victim’s identity becomes entrenched in a controlled victimhood. The intergenerational consequences are highlighted through the two children: a preschool‑age boy with ASD and severe screen addiction, and a mid-teen boy with screen addiction, ADHD and social withdrawal.

The findings emphasize HRV not only as a biomarker of autonomic compromise in IPV survivors but also as a potential tool for clinical monitoring of trauma interventions. The case underscores the necessity of integrating physiological measures into trauma-informed care, and the urgency of addressing safety, intergenerational risk, and systemic barriers to protection.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence (IPV); heart rate variability (HRV); trauma; autonomic dysregulation; behavioral addiction; intergenerational trauma; vagal withdrawal; case study; screen addiction

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health and human rights crisis. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) estimates that approximately one in three women worldwide experience physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner during their lifetime. IPV is associated not only with immediate risks of injury and death but also with long-term sequelae including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and a spectrum of psychosomatic illnesses. (Campbell, 2002; Devries et al., 2013)

Yet, the psychophysiological consequences of IPV remain underexplored in clinical practice. Recent advances in trauma research have highlighted autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysregulation as a central pathway linking chronic threat exposure to psychiatric and somatic disease (Fink et al., 2023; Kolacz et al., 2019, 2020, 2025; Thayer & Lane, 2000). Heart rate variability (HRV), a non-invasive measure of vagal tone and autonomic balance, has emerged as a robust biomarker of stress resilience and allostatic load (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Low HRV, particularly reduced high-frequency (HF) power and root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), reflects diminished parasympathetic regulation and is consistently observed among survivors of IPV and complex trauma (Fink et al., 2023; V. R. Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025).

The theoretical framing of IPV as a pathological homeostasis offers deeper explanatory power. Building on Herman’s (1992) concept of “captivity” notion of trauma reenactment, contemporary models suggest that both aggressor and victim contribute – albeit asymmetrically – to a self-reinforcing cycle. (Campbell, 2002; Devries et al., 2013; Herman, 2015) The aggressor’s violent outbursts function akin to a behavioral addiction, temporarily alleviating inner dysphoria, while the victim’s identity becomes intertwined with controlled victimhood, sustaining relational stability through suffering (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014). This dyadic system is further perpetuated by cultural, legal, and economic barriers that restrict the victim’s autonomy.

In addition to the personal toll, IPV exerts profound intergenerational effects. Children raised in violent households face elevated risks of developmental delays, psychiatric disorders, and perpetuation of violence in adulthood (Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, 2008). Exposure to chronic stress reshapes neurodevelopmental trajectories, with consequences evident in conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit disorder (ADHD), and maladaptive coping through technology overuse. (Manolova et al., 2025, 2025, 2025; Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025, 2025; Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025, 2025; Pashina et al., 2025; Petrov et al., 2025; Petrova et al., 2025; Vezenkov & Manolova, 2025))

This article presents a rare integration of qualitative clinical case material and quantitative HRV analysis in a survivor of chronic IPV. The dual focus allows us to:

- Demonstrate how HRV reflects the embodied consequences of sustained trauma.

- Situate the findings within theoretical models of trauma homeostasis.

- Highlight intergenerational impacts on child development.

- Discuss implications for trauma-informed clinical practice and systemic interventions.

By bridging psychophysiology and psychosocial theory, the case underscores IPV as not only a social or psychological issue but as a measurable physiological condition demanding integrative approaches to treatment and protection.

Theoretical Framework

Intimate Partner Violence as Pathological Homeostasis

The phenomenon of intimate partner violence (IPV) has long been studied through psychological, sociological, and criminological lenses. Traditional frameworks emphasize either the perpetrator’s pathology or the victim’s vulnerability. However, more recent integrative models conceptualize IPV as a pathological homeostasis sustained by dyadic dynamics (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

From this perspective, IPV is not a random sequence of violent acts but a system of mutual reinforcement, where both partners – albeit asymmetrically – participate in the maintenance of a destructive equilibrium. The perpetrator’s aggression often assumes the qualities of a behavioral addiction, functioning as an automatic mechanism for regulating inner dysphoria, frustration, or loss of control (Davis, 2025). Violence, in this sense, becomes a recurring stimulus that reduces emotional overdrive temporarily, much like addictive substances provide relief for craving.

On the other side, the victim may unconsciously adopt an identity of controlled victimhood, characterized by dependent, histrionic, or vulnerable-narcissistic traits. Judith Herman (2015) describes this as an identity built upon suffering: victimization becomes a symbolic currency through which dignity and meaning are negotiated when autonomy is blocked. In this frame, suffering provides moral superiority, allowing the victim to sustain a fragile self-esteem while remaining bound to the aggressor.

Thus, IPV can be seen as a closed cycle of interdependence: the aggressor alleviates dysphoria through violence, and the victim stabilizes self-concept through suffering. Each new episode of aggression simultaneously relieves the perpetrator’s inner tension and reinforces the victim’s narrative of endurance. The relationship persists not despite violence, but through it.

Trauma Reenactment and the Compulsion to Repeat

Bessel van der Kolk (2014) famously articulated the concept of the “compulsion to repeat” trauma. Survivors of early abuse often unconsciously reenact the original trauma in adulthood, recreating dynamics of powerlessness and violation. This is mediated by limbic hyperactivation and deficits in prefrontal inhibition, leading to a neurological predisposition toward re-entering abusive cycles (Ford & Courtois, 2013).

In IPV, trauma reenactment may operate at both individual and dyadic levels. For the aggressor, childhood exposure to violence predicts a higher likelihood of becoming a perpetrator, suggesting a behavioral inheritance of aggression (Widom, 1989). For the victim, internalized patterns of subjugation and submission may predispose to relational choices that replicate earlier trauma. The result is a trauma-driven homeostasis, where both partners unconsciously sustain the abusive cycle.

Autonomic Nervous System Dysregulation in IPV

While psychodynamic and relational theories provide explanatory depth, they must be complemented by psychophysiological evidence. Chronic IPV exposure has profound effects on the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Research consistently demonstrates:

- Reduced vagally mediated HRV indices (low HF power, low RMSSD) in IPV survivors (Fink et al., 2023).

- Blunted long-term HRV complexity, with detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) showing rigid short-term persistence and reduced long-term correlations (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

These alterations constitute a physiological signature of trauma: the body remains in a state of persistent threat readiness, unable to downregulate even during rest or sleep. As noted in experimental paradigms, IPV survivors show exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity to mild stressors and delayed recovery, marking them as vulnerable to both psychiatric and cardiovascular disorders (Davis, 2025; Widom, 1989).

Particularly striking is the finding that nocturnal HF-HRV remains suppressed in IPV survivors, even though parasympathetic dominance should normally reassert itself during sleep. This “autonomic encapsulation” reflects a nervous system that never truly exits survival mode, leaving the individual physiologically trapped in vigilance.

Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma

The consequences of IPV extend beyond the dyad into the lives of children. Exposure to domestic violence during childhood is strongly associated with later psychopathology, including depression, PTSD, and conduct problems (Berg et al., 2022; Evans et al., 2008). Moreover, IPV shapes neurodevelopmental trajectories by embedding stress into physiological systems.

Children exposed to chronic violence often exhibit:

- Heightened sympathetic tone and reduced HRV, mirroring the dysregulation of their caregivers (McLaughlin et al., 2014).

- Difficulties in self-regulation and executive functioning, predisposing to ADHD-like symptomatology (Sroufe, 2005).

- Maladaptive coping behaviors, including excessive screen use and social withdrawal, as substitutes for safe relational regulation (Twenge & Campbell, 2018).

In the presented case, the younger child’s autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and screen addiction, and the older child’s attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), screen addiction and social withdrawal, can be interpreted not only as isolated diagnoses but also as manifestations of trauma-saturated development. The parental relationship’s pathological homeostasis thus reproduces itself intergenerationally, perpetuating cycles of dysregulation.

IPV, Personality Organization, and Addiction Models

IPV can also be conceptualized through the lens of personality organization and addiction models. According to ICD-11, relationally bound personality disorders may manifest as mixed-type organizations, combining dependent, histrionic, and narcissistic features in the victim, and behavioral addiction in the perpetrator.

The perpetrator’s aggression functions as a compulsive behavior, triggered by dysphoric states (e.g., financial loss, gambling defeat, jealousy) and reinforced by the temporary relief it brings. This mirrors the cycle of craving, acting out, and withdrawal in substance use disorders (Goodman, 2008; V. R. Manolova & Vezenkov, 2025). Conversely, the victim’s endurance of suffering serves as a narcissistic stabilizer, allowing her to perceive herself as morally superior while remaining trapped.

This model challenges simplistic binaries of “power versus helplessness” and instead highlights a mutually reinforcing pathology. Such a view does not absolve the perpetrator of responsibility but emphasizes the systemic and cyclical nature of IPV.

IPV, HRV, and Biomarkers of Trauma

Bringing these threads together, HRV emerges as a biomarker of pathological homeostasis. Survivors of IPV consistently demonstrate:

- Reduced RMSSD (<30 ms)

- Suppressed HF-HRV during sleep

- Low total power (<1000 ms² at rest)

These indices correspond to what Fink et al. (2023) describe as a sympathovagal imbalance, and what Fink et al. (2023) call a physiological footprint of IPV. In clinical practice, HRV allows for objective measurement of trauma’s embodied impact and provides a tool for monitoring recovery during interventions such as trauma-focused CBT, EMDR, or HRV biofeedback (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). While LF/HF was elevated, we interpret it cautiously, given ongoing debate about its specificity; our primary inference of vagal withdrawal rests on converging reductions in RMSSD, HF power, and total power.

Thus, IPV is not only a social or psychological phenomenon but also a biologically measurable condition, with HRV offering a window into the invisible scars of trauma.

Summary of Theoretical Framework

- IPV represents a pathological homeostasis sustained by aggression-as-addiction and victimhood-as-identity.

- Trauma reenactment explains the persistence of abusive cycles across time and generations.

- ANS dysregulation, measured through HRV, reveals vagal withdrawal, sympathetic dominance, and reduced adaptability.

- Children of IPV households embody intergenerational trauma, with developmental, behavioral, and physiological consequences.

- HRV can function as a biomarker for both diagnosis and monitoring of trauma-related conditions.

This theoretical scaffolding grounds the subsequent case presentation, where psychophysiological data are integrated with clinical narrative to illustrate how IPV imprints itself across the body, psyche, and family system.

Case Presentation

Demographic and Family Background

The subject of this case study is a 38-year-old married woman who has endured 20 years of continuous intimate partner violence (IPV). She lives with her husband and their two children: a mid-teen adolescent boy and a preschool‑age boy. The family resides in conditions of chronic economic deprivation, with recurrent financial instability linked to the father’s gambling addiction.

The marriage began when the woman was 18 years old, suggesting an early entrapment into the relationship with limited autonomy and minimal social or economic capital. Over the course of two decades, she has remained in the household despite sustained violence, citing lack of personal resources, housing, and income as primary barriers to leaving. She also expresses fear of losing custody of her children, as the father has threatened to retain them if she attempts separation.

Profile of the Aggressor

The husband exhibits a consistent pattern of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. Severe physical assaults occur weekly or biweekly, involving punches, kicks, and beatings with objects such as belts. In addition, daily “minor” assaults are reported, including slaps, throwing objects, and verbal degradation.

Sexual coercion is a central dimension: when the woman refuses intercourse, she is physically assaulted and raped by her husband. Over the course of the marriage, she has endured more than ten abortions, eight of which were induced, while the remainder were spontaneous miscarriages attributed to stress and physical injury.

The aggressor himself denies any problem. He describes the family as “well” and perceives no need for medical or therapeutic intervention for the children. By contrast, the woman characterizes him as gambling-dependent, with a cycle in which gambling losses precipitate the most violent episodes. After violent outbursts, he tends to calm down and enter periods of apparent good mood, consistent with the tension-release-reward cycle seen in behavioral addictions (Goodman, 2008).

Psychological and Somatic Impact on the Mother

The mother presents with signs of severe chronic trauma:

- Physiological arousal: resting tachycardia, inability to relax, startle responses.

- Trauma-linked phobias: inability to close her eyes during HRV testing, panic upon exposure to complete darkness in the laboratory setting.

- Somatic exhaustion: periods of immobilization after beatings, during which she remained bedridden for days.

- Psychosexual trauma: repeated marital rape with associated emotional numbing.

- Reproductive trauma: 15+ abortions/miscarriages, representing both medical and psychological scarring.

During HRV testing, she was unable to tolerate conditions of darkened environment, exhibiting acute panic episode upon blackout. Such a reaction underscores hypervigilance and phobic avoidance, hallmarks of chronic PTSD (Nemeroff, C.B. et al., 2022).

The Older Child: A mid‑teen with ADHD

The adolescent boy has symptoms of ADHD and screen addiction accompanied by social withdrawal and affective instability. He displays:

- Atypical peer relations: he has no friends, isolates himself in his room, and spends most of his non-school hours playing on his phone.

- School instability: he has changed schools multiple times due to conflicts with teachers and peers, which the mother interprets as bullying and teacher hostility.

- Anxiety and somatic symptoms: he experiences tics (notably eye blinking) and heightened reactivity to stress.

- Maladaptive coping: during episodes of IPV, he leaves the household, wandering the streets, and sometimes not returning until the following morning. The mother has occasionally found him asleep on the street, underscoring both his avoidance of domestic violence and his exposure to environmental danger.

Psychodynamically, the adolescent appears to oscillate between over-identification with the victimized mother and avoidant detachment, both maladaptive responses to chronic IPV exposure (Sroufe, 2005). His panic-like responses to the younger sibling’s crying suggest unresolved trauma triggers linked to auditory stress and helplessness.

The Younger Child: A preschool‑age with ASD

The younger child is a boy diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), presenting as non-verbal, hyperactive, and aggressive. His developmental environment is characterized by both screen addiction (excessive screen exposure 6+ hours daily) and early expulsion from kindergarten due to aggressive behavior toward peers and teachers.

Clinically, the child demonstrates:

- Severe screen addiction, with tantrums and aggression when deprived of devices.

- Hyperarousal and aggression, consistent with both ASD features and environmental overstimulation.

- Parental neglect, as the mother – overwhelmed by trauma and caregiving stress – relies on screens for behavioral control.

From an intergenerational trauma lens, the child embodies somaticized dysregulation, where both neurodevelopmental vulnerability (ASD) and environmental trauma converge. Chronic exposure to IPV during critical developmental windows may exacerbate his difficulties with self-regulation and attachment (Feldman, 2007).

Social Context and Institutional Responses

The case is further complicated by systemic failures. On multiple occasions, neighbors have called the police during severe assaults. While warning protocols have been issued to the husband, no criminal charges or protective measures have followed. This institutional inertia perpetuates the cycle of violence, leaving the victim without meaningful protection.

Economic deprivation compounds vulnerability: the husband’s gambling consumes household resources, ensuring perpetual poverty and dependency. This financial instability undermines the mother’s capacity to plan escape and sustains her learned helplessness (Davis, 2025; Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

Integrative Clinical Picture

This case illustrates IPV as a multilayered syndrome:

- At the individual level (the mother):

- Severe PTSD-like symptoms (hypervigilance, panic in darkness, startle responses).

- Somatic sequelae (immobilization, reproductive trauma).

- Psychophysiological dysregulation (evidenced by HRV).

- At the partner-dyad level:

- The husband’s aggression as a behavioral addiction, tied to gambling and emotional dysregulation.

- The wife’s victimhood as identity, perpetuating the relational homeostasis.

- At the intergenerational level:

- Older child: ADHD symptoms, screen addiction symptoms, social withdrawal, trauma-reactive avoidance.

- Younger child: ASD, screen addiction symptoms, aggression.

- At the systemic level:

- Institutional passivity (ineffective police response).

- Structural barriers (poverty, lack of shelter, absence of accessible child services).

Clinical Significance

This case underscores the intersection of IPV, psychophysiology, and intergenerational trauma. It illustrates how IPV is not confined to the realm of interpersonal violence but functions as a systemic disorder with biological markers, psychological patterns, and social consequences. The HRV data offer objective confirmation of the embodied toll of trauma, while the children’s developmental trajectories reveal the reproduction of trauma across generations.

Methods

Study Design

This case report employs a single-subject psychophysiological design integrating qualitative clinical data with quantitative autonomic indices. The primary aim was to assess the impact of chronic IPV on autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation, as measured through heart rate variability (HRV). The study situates HRV data within the broader psychosocial and clinical context of the survivor and her family system.

Participant

The participant is a 38-year-old woman exposed to 20 years of continuous IPV, including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. She presented with severe trauma-related symptoms (panic in darkness, hypervigilance, recurrent immobilization after assaults). Her background, family structure, and intergenerational context are described in detail in the Case Presentation section.

Procedure

Peripheral autonomic nervous system signals were recorded using the GP8 Amp 8-channel biofeedback amplifier and Alive Pioneer Plus software (Somatic Vision Inc., USA). The parameters assessed included: Heart Rate (HR); Heart Rate Variability (HRV); Peripheral Skin Temperature; Respiratory Rate; Skin Conductance Level (SCL); Surface Electromyography (EMG); HRV indices – such as SDNN (standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals), total power, LF/HF ratio, stress index, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) index, and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) index – were first analyzed in Alive Pioneer Plus and then exported for further processing in Kubios HRV Scientific Lite software (University of Eastern Finland).

Short‑term HRV was recorded for 5 min in seated rest between 9:00-17:00, with 30 min acclimation; participants abstained from caffeine, nicotine, and vigorous exercise for 12 h. Signals were sampled at 1 kHz for HRV analysis. Artifact correction used Kubios HRV v3.4.1, threshold 15%, ectopic removal on (cubic spline interpolation). Spontaneous respiration was measured via a respiratory inductance (RIP) belt (16 Hz sampling); no paced breathing was used.

Due to panic reactions in full darkness, measurements were taken in a dimly lit room with eyes open. Eye-closure and complete blackout trials were attempted but discontinued due to acute panic reactions.

Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitivity of IPV contexts, informed consent was obtained with full explanation of procedures. Due to the acute trauma reactions observed, participant safety and comfort were prioritized: sessions were terminated immediately upon distress, and the minimal recording condition was chosen to avoid retraumatization. All identifying details have been anonymized.

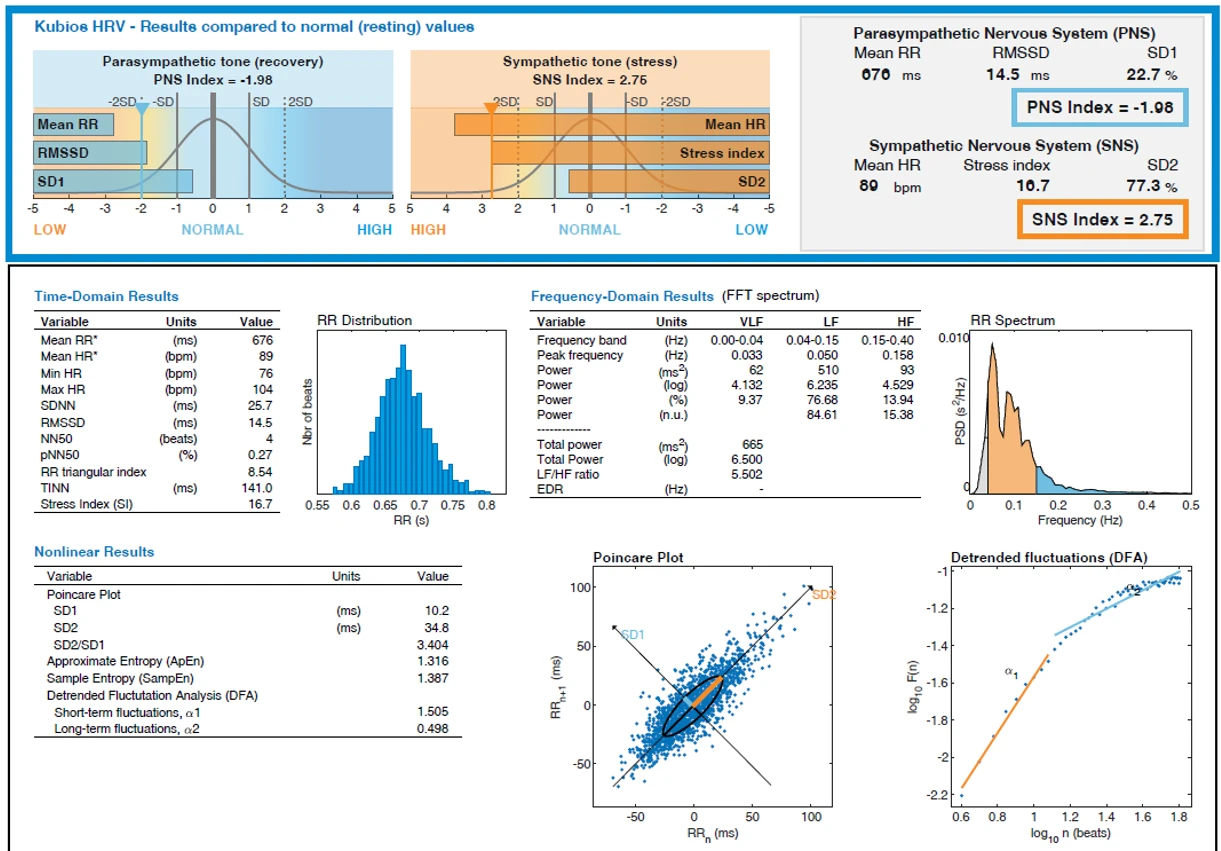

Results

The mother’s HRV analysis at rest (eyes open) is displayed in Figure 1. The figure presents an overview of heart rate variability results. It includes autonomic indices for parasympathetic and sympathetic activity, time-domain parameters, frequency-domain spectra, and nonlinear metrics. Graphical displays show the RR interval distribution, power spectral density, Poincaré plot, and detrended fluctuation analysis.

Figure 1. HRV Indices and Metrics (Time-, Frequency-, and Nonlinear-Domain)

Autonomic Indices

- Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) Index: −1.98

- Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) Index: +2.75

These values deviate by more than two standard deviations from normative baselines, indicating suppressed vagal tone and hyperactive sympathetic drive.

Time-Domain Metrics

- Mean RR interval: 676 ms

- Mean Heart Rate: 89 bpm (range: 76–104 bpm)

- SDNN: 25.7 ms (low variability)

- RMSSD: 14.5 ms (markedly reduced vagal modulation)

- NN50: 4 beats; pNN50:27%

- RR Triangular Index: 8.54

- TINN: 141 ms

- Stress Index:16.7

These findings confirm low beat-to-beat variability, consistent with restricted adaptability under resting conditions. The stress index is significantly elevated, reflecting chronic sympathetic dominance.

Frequency-Domain Metrics

- VLF Power (0.00–0.04 Hz): 62 ms² (9.37%)

- LF Power (0.04–0.15 Hz): 510 ms² (76.68%; 84.61 n.u.)

- HF Power (0.15–0.40 Hz): 93 ms² (13.94%; 15.38 n.u.)

- Total Power: 665 ms²

- LF/HF Ratio: 5.50

Nonlinear Dynamics

- SD1: 10.2 ms

- SD2: 34.8 ms

- SD2/SD1 Ratio: 3.40

- Approximate Entropy (ApEn):1.32

- Sample Entropy (SampEn):1.39

- DFA α1 (short-term):1.505 (rigid persistence)

- DFA α2 (long-term): 0.498 (blunted correlations)

The Poincaré plot revealed a narrow ellipse (low SD1) elongated along the identity line (SD2), suggesting long-term variance without short-term flexibility. Entropy indices were reduced, consistent with loss of complexity in physiological dynamics.

Graphical Outputs

- RR interval distribution: Narrow with reduced spread, indicating rigidity.

- Power spectral density curve: Dominant LF peak at 0.050 Hz; minimal HF shoulder at 0.158 Hz.

- Poincaré scatter: Narrow cross-beat width with elongated ellipse.

- DFA plot: Steep α1 slope (>1.5) and flattened α2 slope (~0.5).

Integrative Interpretation

The HRV results converge on the following profile:

- Elevated resting HR (89 bpm) despite quiet conditions.

- Low RMSSD and HF power, showing suppressed vagal input.

- Reduced total power and entropy, reflecting diminished overall capacity for adaptive regulation.

- Rigid short-term control and blunted long-term coherence (DFA findings).

This profile is typical of survivors of chronic IPV and trauma exposure. It reflects a nervous system in persistent survival mode, unable to downshift even in a controlled environment.

Clinical Correlation

These physiological findings mirror the clinical presentation:

- Inability to close eyes during testing → consistent with hypervigilance and fear of vulnerability.

- acute panic episode upon darkness → physiological readiness for threat.

- Resting tachycardia and high sympathetic tone → chronic “fight-or-flight” baseline.

- Reduced HRV complexity → diminished resilience to stressors, explaining panic, sleep fragmentation, and emotional lability.

Together, HRV data and clinical history provide objective confirmation of embodied trauma.

Discussion

HRV as a Biomarker of Trauma in IPV Survivors

The HRV findings in this case demonstrate a classical pattern of vagal withdrawal, sympathetic dominance, and reduced autonomic complexity, consistent with the broader literature on trauma and IPV (Berg et al., 2022; Davis, 2025; Fink et al., 2023). Specifically, the participant’s low RMSSD (14.5 ms), and reduced total power (665 ms²) align with meta-analyses reporting systematic suppression of parasympathetic indices in women exposed to intimate partner violence. While LF/HF was elevated, we interpret it cautiously, given ongoing debate about its specificity; our primary inference of vagal withdrawal rests on converging reductions in RMSSD, HF power, and total power. These physiological signatures extend beyond subjective accounts of stress, offering an objective biomarker of trauma-related dysregulation.

Importantly, the participant’s inability to tolerate darkness or eye closure during testing underscores how trauma imprints on basic sensory regulation. Hypervigilance is not merely a psychological phenomenon but a bodily imperative encoded in the autonomic system. As van der Kolk (2014) argues, “the body keeps the score”: physiological rigidity reflects the survivor’s ongoing entrapment in survival states, even in safe laboratory conditions.

IPV as Pathological Homeostasis

This case further illustrates IPV as a dyadic pathology, wherein violence is not accidental but constitutive of relational homeostasis. The aggressor’s violent outbursts mirror behavioral addiction, providing temporary relief from dysphoric states (e.g., gambling losses), while the victim’s endurance reinforces a victimhood identity, granting fragile moral superiority.

From a systems perspective, both partners are locked in a self-reinforcing loop: aggression relieves the perpetrator’s tension, while suffering validates the victim’s endurance. The HRV findings of chronic sympathetic activation can thus be seen not only as the physiological imprint of trauma but also as the embodied marker of relational pathology.

Intergenerational Trauma Transmission

The two children in this family vividly demonstrate the intergenerational effects of IPV. Research confirms that children exposed to domestic violence exhibit altered stress physiology, with heightened sympathetic tone and reduced HRV (Berg et al., 2022; McLaughlin et al., 2014). Over time, these alterations manifest as psychiatric and developmental vulnerabilities.

In this case:

- The older child (mid-teen) presents with ADHD symptoms, screen addiction symptoms, anxiety, and social withdrawal. His panic responses to the younger sibling’s crying reflect trauma triggers, suggesting secondary traumatization. His avoidance behaviors (spending nights outside after IPV episodes) indicate both self-preservation and environmental risk.

- The younger child (preschool‑age), with ASD and severe aggression, demonstrates screen addiction as a substitute for relational regulation. In the absence of parental attunement, digital devices become pseudo-soothing objects (Twenge & Campbell, 2018), reinforcing isolation and impairing developmental socialization.

These outcomes highlight how IPV not only damages the direct victim but also reconfigures child development, embedding trauma into future generations.

The Role of Screen Addiction in Family Pathology

Both children show signs of severe screen addiction – a feature particularly concerning in this context. Screen addiction serves multiple dysfunctional functions:

- Regulation substitute: In a household devoid of safe co-regulation, screens act as external regulators of distress. For the younger child, excessive video content provides sedation; for the older child, digital immersion offers escape.

- Avoidance of family reality: Both children retreat into screens to block out the violence and chaos of the household.

- Interference with development: Excessive screen use exacerbates core symptoms of ASD and ADHD, including hyperactivity, attentional difficulties, and social withdrawal (Domingues‐Montanari, 2017).

The father’s conviction that therapy is unnecessary compounds the issue. His denial functions as an extension of the broader pathological homeostasis, wherein acknowledging dysfunction would destabilize the relational system. By insisting that “the children are fine,” he legitimizes neglect and blocks therapeutic interventions that could break the cycle. This parental minimization is itself a form of abuse: denying children access to therapy is tantamount to denying them the possibility of regulation and recovery.

Institutional and Structural Failures

Despite multiple police interventions, no protective measures have been enacted. This reflects a structural failure common in IPV contexts: institutions issue warnings but fail to disrupt the cycle of violence (Devries et al., 2013; Organization, 2021). The absence of systemic support forces survivors into learned helplessness (Davis, 2025; Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

Furthermore, economic deprivation (driven by the father’s gambling) maintains the family in a state of chronic dependency. Poverty not only prevents escape but also amplifies screen addiction in children, as digital devices become the cheapest form of childcare and distraction.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

The findings of this case study highlight a series of pressing clinical imperatives. Above all stands the principle of safety. The HRV data unmistakably reveal ongoing autonomic harm; as long as the survivor remains in a violent environment, trauma-focused therapies carry the risk of retraumatization rather than healing. Stabilization and protection, therefore, must precede any attempt at deeper psychological intervention.

Equally urgent is the need for integrated child support. Both children in the household exhibit severe dysregulation: the younger child with autism spectrum disorder requires intensive behavioral therapy and reduction of screen exposure, while the older adolescent with attention-deficit disorder needs structured treatment that addresses both attentional deficits and social withdrawal. In both cases, therapeutic work must include specific interventions targeting screen addiction, while since screen overuse functions as a maladaptive regulator that exacerbates their developmental vulnerabilities.

The father’s refusal to acknowledge the children’s needs underscores the issue of parental accountability. His denial effectively blocks access to therapeutic care and perpetuates neglect, which makes the involvement of external systems essential. Child protection services and judicial structures are necessary to override such neglect and ensure that the children receive adequate support.

For the mother, trauma-informed care offers the only sustainable path toward recovery. What is required is a phased approach that begins with stabilization, proceeds to trauma processing, and ultimately works toward reintegration. Adjunctive methods such as HRV biofeedback could be especially valuable, given her marked vagal withdrawal and sympathetic dominance. These interventions can help restore autonomic flexibility, supporting her capacity to regulate emotions and tolerate stress.

Finally, the case illustrates the broader necessity for systemic reform. Current institutional practices – such as the issuing of warning protocols without enforceable follow-up – prove inadequate in breaking the cycle of IPV. Effective protection requires the implementation of binding protective orders, the availability of shelters, and a reorientation of law enforcement toward survivor safety rather than procedural formalities.

Conceptual Integration

Taken together, the evidence positions intimate partner violence as a complex biopsychosocial disorder, sustained by the pathological homeostasis between aggressor and victim. It is simultaneously a physiological condition, objectively measurable through heart rate variability, and an intergenerational trauma system that transmits itself through both psychodynamic mechanisms and developmental neglect. Within this ecology, the children’s screen addiction emerges not as a trivial behavioral problem but as a maladaptive survival mechanism, a substitute for the absent co-regulation of safe caregivers.

In this sense, IPV is revealed as more than an individual or relational problem: it is a total ecology in which the body, the psyche, the children, and the surrounding institutions become entangled in cycles of violence, denial, and systemic failure. Only by recognizing the interwoven biological, psychological, and social dimensions of this ecology can clinicians, policymakers, and communities begin to dismantle the structures that sustain such suffering.

Conclusion

This case study demonstrates the profound impact of chronic intimate partner violence on psychophysiological regulation, psychological functioning, and intergenerational well-being. Through the integration of qualitative narrative and quantitative heart rate variability analysis, the findings reveal a nervous system trapped in survival mode, marked by vagal withdrawal, sympathetic dominance, and diminished complexity. These physiological signatures are not isolated indicators but rather embodied reflections of the lived trauma described by the participant.

By situating the case within contemporary theoretical frameworks, IPV emerges as a form of pathological homeostasis, maintained by the aggressor’s compulsive violence and the victim’s controlled victimhood. This dynamic perpetuates itself not only within the dyad but across generations, as evidenced by the children’s developmental difficulties and maladaptive reliance on screens as substitutes for relational regulation. The father’s denial of therapeutic needs further illustrates how minimization and neglect actively sustain the cycle, while institutional passivity reinforces the structural conditions that prevent escape.

From a clinical standpoint, the case underscores the necessity of prioritizing safety before trauma-focused interventions, while simultaneously ensuring integrated child support. HRV emerges as a promising biomarker for both diagnosis and progress monitoring, linking subjective suffering with objective physiological evidence. The broader implication is that IPV should be approached not only as a psychological or social crisis but as a measurable physiological condition, requiring interventions that address the full ecology of trauma: body, psyche, family, and institutions.

Ultimately, this study calls for systemic reform. Survivors cannot be expected to heal while institutions fail to provide enforceable protection or adequate child services. IPV is not simply a private tragedy; it is a public health crisis with biological, psychological, and intergenerational consequences. Recognizing IPV as such opens the way for integrated, trauma-informed, and justice-oriented responses that can disrupt cycles of suffering and create conditions for genuine recovery.

References

Berg, K. A., Evans, K. E., Powers, G., Moore, S. E., Steigerwald, S., Bender, A. E., Holmes, M. R., Yaffe, A., & Connell, A. M. (2022). Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Children’s Physiological Functioning: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Family Violence, 37(8), 1321–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00370-0

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

Davis, T. (2025). Cortisol Dysregulation and the Trauma Cycle in Intimate Partner Violence Survivors. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Neurology, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.61440/JCPN.2025.v3.39

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., García-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Lim, S., Bacchus, L. J., Engell, R. E., Rosenfeld, L., Pallitto, C., Vos, T., Abrahams, N., & Watts, C. H. (2013). The Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women. Science, 340(6140), 1527–1528. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240937

Domingues‐Montanari, S. (2017). Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 53(4), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462

Evans, S. E., Davies, C., & DiLillo, D. (2008). Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005

Feldman, R. (2007). Parent–infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x

Fink, B. C., Claus, E. D., Cavanagh, J. F., Hamilton, D. A., & Biesen, J. N. (2023). Heart rate variability may index emotion dysregulation in alcohol-related intimate partner violence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1017306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1017306

Ford, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2013). Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. Guilford Press.

Goodman, A. (2008). Neurobiology of addiction. Biochemical Pharmacology, 75(1), 266–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.030

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence--From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Hachette UK.

Kolacz, J., Dale, L. P., Nix, E. J., Roath, O. K., Lewis, G. F., & Porges, S. W. (2020). Adversity History Predicts Self-Reported Autonomic Reactivity and Mental Health in US Residents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 577728. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577728

Kolacz, J., Kovacic, K. K., & Porges, S. W. (2019). Traumatic stress and the autonomic brain‐gut connection in development: Polyvagal Theory as an integrative framework for psychosocial and gastrointestinal pathology. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(5), 796–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21852

Kolacz, J., Tabares, J. V., Roath, O. K., Rooney, E., Secor, A., Nix, E. J., Tomlinson, C. A., & Bryan, C. J. (2025). Dynamics of PTSD and autonomic symptoms in a longitudinal U.S. population-based sample. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001918

Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Manolova, V., Pashina, I., Mateev, M., & Vezenkov, S. (2025). Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy and Other Forms of Parental Abuse in Children with Screen Addiction and a Diagnosis of Autism (ASD) and/or ADHD. Nootism, 1(2), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.2.2

Manolova, V. R., & Vezenkov, S. R. (2025). Unified Trauma-Addiction Functioning Model. Nootism, 1(4), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.4.1

Manolova, V., & Vezenkov, S. (2025). Parental Models: A Profile of the Dynamics in Children Dropping Out of Therapy Programs for Screen Addiction. Nootism, 1(1), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.11

McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2014). Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012

Nemeroff, C.B., Alan F. Schatzberg M.D, Natalie Rasgon, M. D. Ph.D, & Stephen M. Strakowski M.D. (2022). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Mood Disorders, Second Edition. American Psychiatric Pub.

Organization, W. H. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization.

Pashina, I., Manolova, V., & Vezenkov, S. (2025). Parental Recovery as a Key Factor for the Recovery of Children with Screen Addiction – Biofeedback Therapy for Severe Disorders. Nootism, 1(1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.9

Petrov, P., Manolova, V., & Vezenkov, S. (2025). Hidden Family Dynamics in a Case Study of a Child with Screen Addiction, Hyperactivity, and Language Deficits. Nootism, 1(1), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.10

Petrova, S., Manolova, V., & Vezenkov, S. (2025). Reintroducing Screens: Severe Regression and Symptom Aggravation in Children with ASD/Screen Addiction. Nootism, 1(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.2NCSC.5

Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00338-4

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma (pp. xvi, 443). Viking.

Vezenkov, S., & Manolova, V. (2025). Gaming and Gambling Addiction in Fathers as a Risk Factor for Early Screen Addiction in Children. Nootism, 1(2), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.64441/nootism.1.2.3

Widom, C. S. (1989). The Cycle of Violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2704995